Improving cancer care for Indigenous Australians

Radiation therapists share their insights on the challenges and opportunities serving patients in remote areas

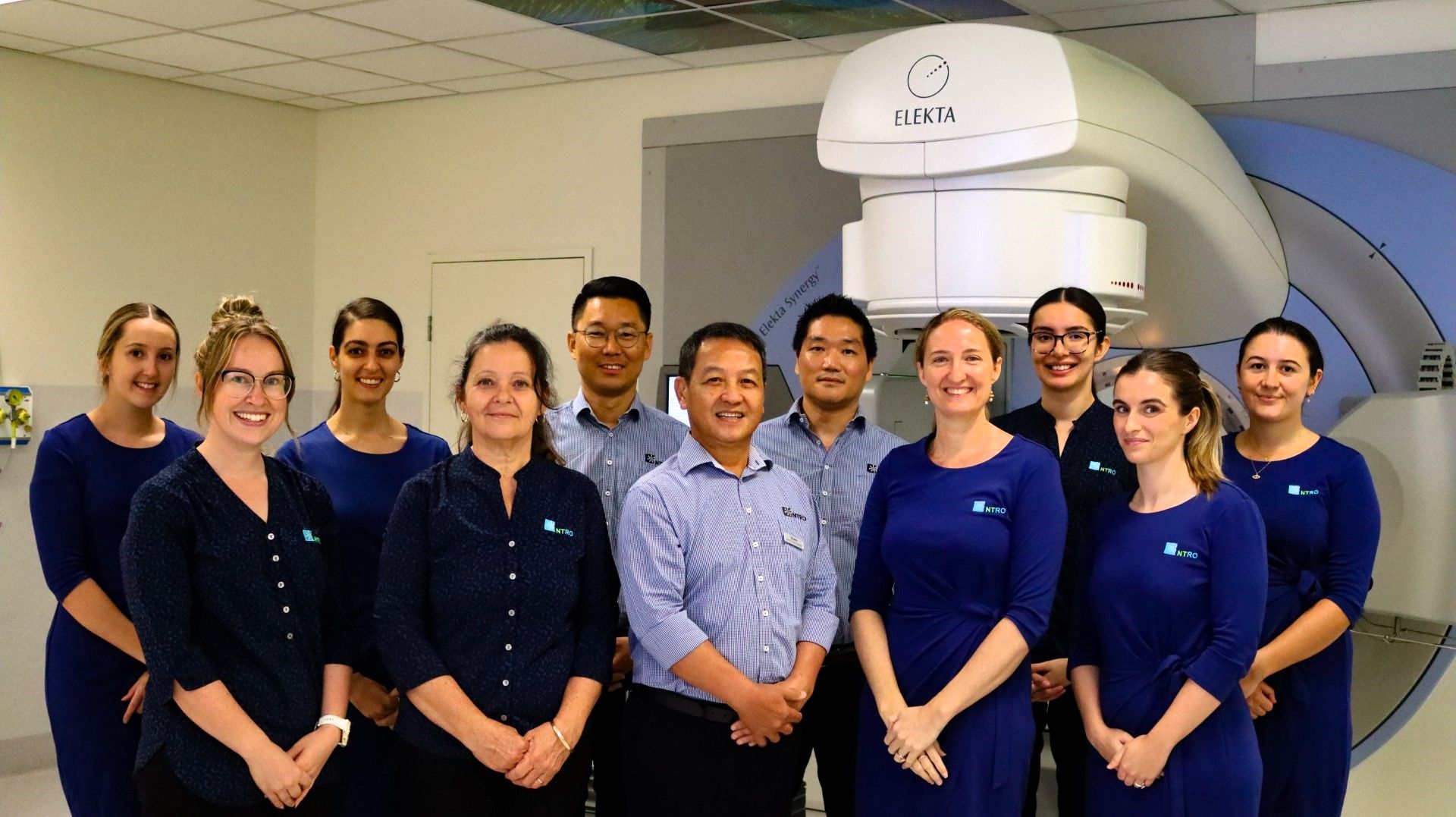

Compared with non-Indigenous persons with cancer, Indigenous patients who live in Australia’s Northern Territory (NT) face a spectrum of challenges, including travel distances, later stage diagnoses, lifestyle factors linked to cancer and profound cultural differences. At Elekta, reducing the cancer care gap and providing hope for more cancer patients is a cornerstone. Below, read how the team at Alan Walker Cancer Care Centre’s (AWCCC) Northern Territory Radiation Oncology (NTRO) is working to get Indigenous cancer patients the help they need and how Elekta has partnered with the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) to award a standout fourth-year Bachelor of Radiation Therapy student the Elekta Prize for Commitment to Improving Australian Indigenous Health (see sidebar: Elekta supports improvement of Indigenous health with annual award).

Enhancing care for Indigenous cancer patients

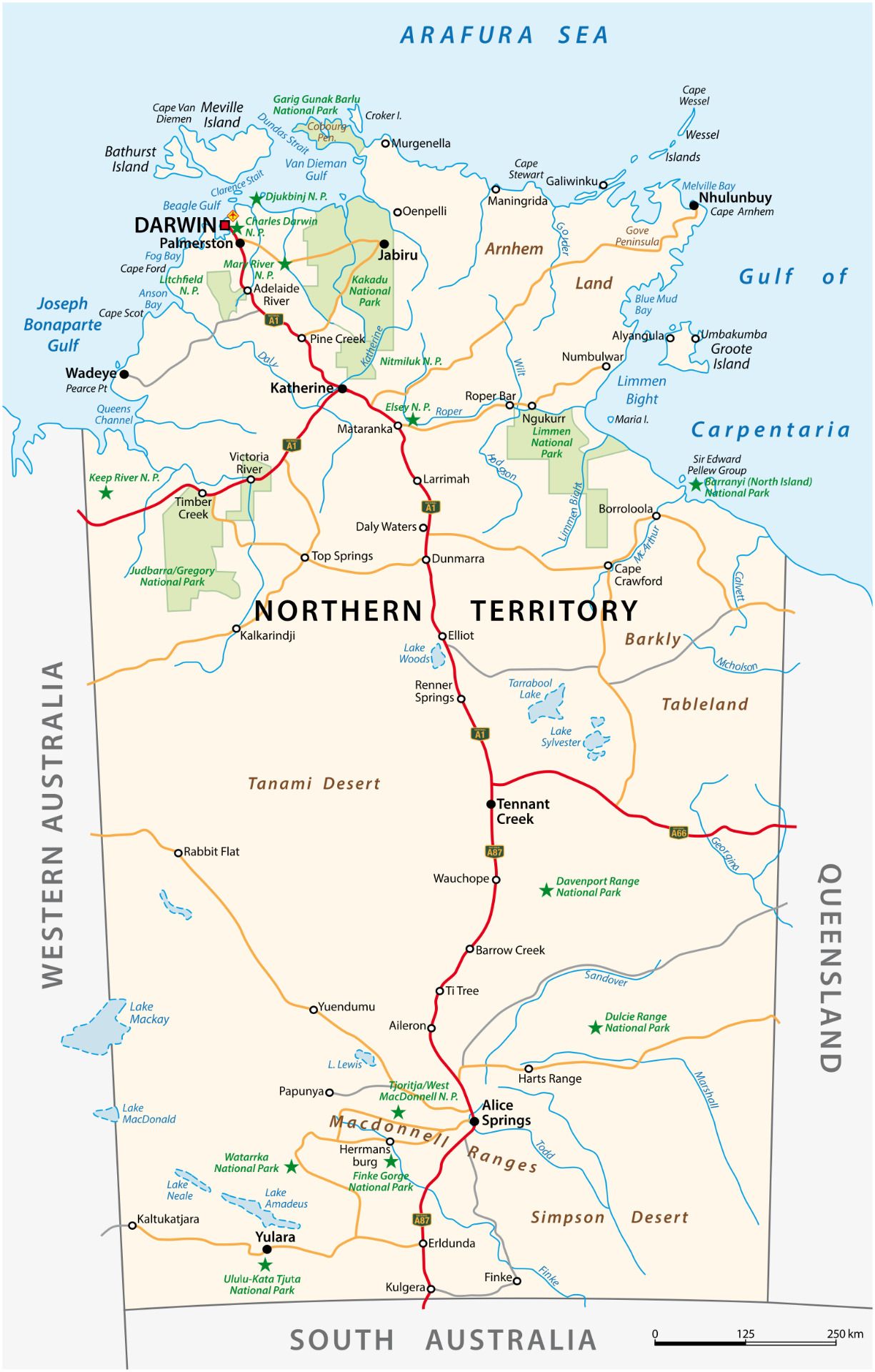

Before AWCCC was established in 2010 at Royal Darwin Hospital, residents in NT had to travel to Adelaide, South Australia, which is 3,029 kilometers from Darwin. Even now that AWCCC has opened, many Indigenous Australians (i.e., Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) may still have to travel hundreds of kilometers from their remote communities to access radiation therapy.

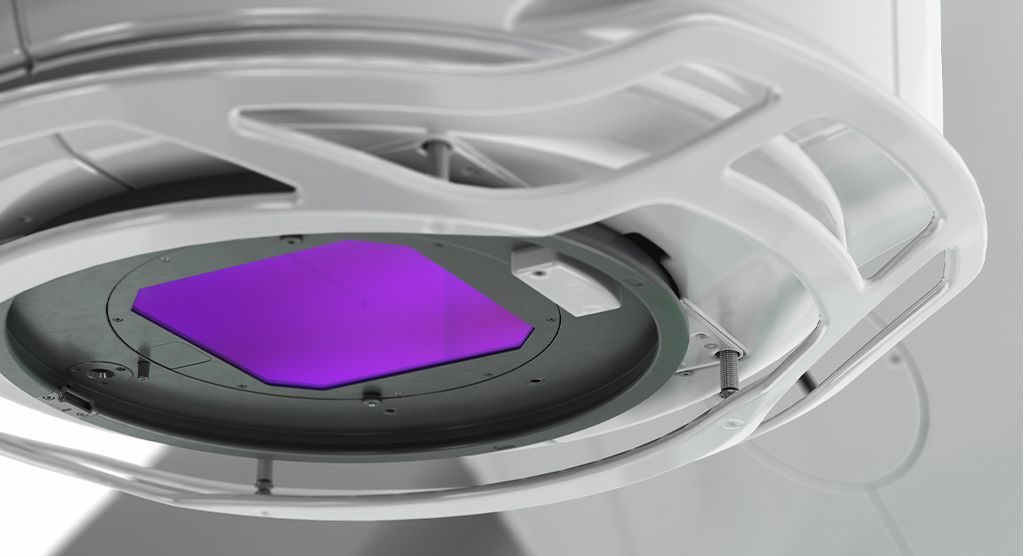

For the last 14 years, NTRO has been working to improve the prospects of Indigenous cancer patients who need radiation therapy. The only linacs in the entire territory, NTRO operates two beam-matched Elekta Synergy® systems, both with HexaPOD™ evo RT robotic positioning system, which will be replaced by a pair of beam-matched Elekta Versa HD™ linacs in 2025. Since 2010, NTRO has treated nearly 5,000 patients with radiotherapy.

Indigenous patients represent about 20 percent of NTRO’s 30 to 35 daily radiation therapy treatments, with lung, liver and head-and-neck cancers most common among Indigenous men and breast, lung and liver most common for women.1

“There is a high incidence of tobacco and alcohol use in some Indigenous communities, and these behaviors are well-known to be linked with many of the cancers we see within the Indigenous population.”

“There is a high incidence of tobacco2 and alcohol use in some Indigenous communities, and these behaviors are well-known to be linked with many of the cancers we see within the Indigenous population,” says Elly Keating, NTRO’s chief radiation therapist.

In general, lower socioeconomic status is linked to a higher cancer risk lifestyle, such as smoking, but there are several other issues that complicate cancer care among Indigenous Australians, according to Emily Hearnden, an NTRO RTT and case planner based at Nhulunbuy, a small East Arnhem Land town with a large population of Indigenous residents 1,042 kilometers east of Darwin. She grew up in the small, remote community of Urapunga, enabling her to have a greater appreciation and understanding of how to provide culturally appropriate care.

“It’s just such a hugely disadvantaged patient population and they face countless barriers,” Hearnden notes. “There is a greater incidence of higher mortality cancers and they’re diagnosed at a later stage since most don’t have access to screening or health services like people in the cities do. Plus, there is a lower cancer literacy rate, not just among the Indigenous patients but also at the health centers.”

NTRO’s outreach concerning cancer education among healthcare professionals in isolated NT community clinics had NTRO Executive Director Giam Kar (retired) educate them on cancer causes and presentation symptoms.

“This was intended to improve the likelihood that if a patient goes into their local clinic and complains of non-stop coughing that cancer is on their radar as a possibility considering their lifestyle factors,” Keating says. “NTRO has done some work in a remote place called Borroloola that had quite poor outcomes and Giam was working to educate their health professionals. In addition, a Cancer Australia initiative employed an Aboriginal/Indigenous nurse with cancer care training to work in the clinic to coordinate care between that community and NTRO.”

Through Hearnden, NTRO is continuing this effort in Nhulunbuy and surrounding areas in the Gove Peninsula.

“I’m working to bring patient education to patients in person before they have to travel to Darwin for radiation therapy.”

“I’m working to bring patient education to patients in person before they have to travel to Darwin for radiation therapy,” she notes. “It will give Indigenous patients an idea of what to expect and build that relationship and work with the local Aboriginal health clinics to provide those education sessions. It could be as straightforward as a one-on-one chat with the patient or their family as well – it’s just nurturing trust and putting a face to what’s going to happen.”

Divergent cultures pose challenges

Beyond a limited understanding of cancer causes and how the disease is treated among Indigenous persons, cultural factors make interacting with and treating Aboriginal patients more challenging, Hearnden says.

“There is definitely a level of distrust, since the majority of their health services are provided by non-Aboriginal people, so it can take a while to build a relationship with the patients to ensure they feel safe,” Hearnden observes. “Culturally safe care is something we work on really hard.”

Keating emphasizes that the nuances of Indigenous culture can’t be learned comprehensively through study.

“We are very lucky to have someone like Emily who has lived in remote Aboriginal communities since she was very young, and so has a connection between western culture and Aboriginal culture.”

“We are very lucky to have someone like Emily who has lived in remote Aboriginal communities since she was very young, and so has a connection between western culture and Aboriginal culture – or, alternatively, you just try your hardest to provide care in the most culturally safe way, even if it’s incorrect some of the time,” she says. “Failing that, just be aware that you’re treating patients with a very complex cultural need. There’s no guidebook on how to treat Indigenous patients that specifies one should avoid this word or that or avoid eye contact – it’s not that easy.”

Even the structure of conversation can differ between western and Indigenous people, Keating adds.

“Western conversations are more give-and-take, whereas an Aboriginal person will often just sit and listen,” she says. “It’s not that they don’t understand, it’s their culture to stay a bit quieter – they don’t necessarily give you those verbal cues that they comprehend what you’re explaining.”

In Hearnden’s experience, she has observed fairly strict male/female segregation, such that if one is dealing with “female-sensitive” situations like gynecological and breast cancers, it can be important to ensure that only female staff address them.

“In the context of Indigenous culture there is generally ‘women’s business,’ in which the women hold certain cultural knowledge and in the same way there is ‘men’s business.”

“In the context of Indigenous culture there is generally ‘women’s business,’ in which the women hold certain cultural knowledge and in the same way there is ‘men’s business,’” she notes. “We need to be mindful of those cultural practices to make the patient feel safe and willing to continue their care with us. It should be noted that Indigenous cultural knowledge is local and specific, and therefore even in NT alone what is considered culturally appropriate can vary from one community to another.

“Additionally, Indigenous people have complex kinship systems,” Hearnden continues. “I have been adopted into the kinship system in East Arnhem Land through my partner, where I now have a direct reciprocal relationship to the local Indigenous people in the area. For instance, I’ll be introduced to someone, and they could be my grandfather even though they’re much younger than I, or they could be my ‘poison cousin’ where I have to avoid them out of respect.”

Many of these aspects of Aboriginal culture are taught to NTRO staff via a mandatory, culturally safe training day given by one or more Aboriginal Liaison Officers (ALO)s.

“These Indigenous facilitators give an overview of Indigenous culture, touching on things like family groups, men’s and women’s business and the reasons for distrust in Western medicine,” Keating explains. “Aside from this, staff gain an understanding of the impacts of colonization and how it has led to the disparity in health outcomes for Indigenous Australians.”

Getting Aboriginal cancer patients to NTRO

Indigenous patients in Nhulunbuy are referred for investigations by a physician, either their local general practitioner or if they are presented to the emergency department. There are basic imaging modalities in the community, such as CT, X-ray and ultrasound, but more complex investigations, such as MRI, PET and biopsies are performed in Darwin. Hearnden’s role comes into play only when the patient has been diagnosed and is referred for radiation therapy.

Regarding travel logistics, Nhulunbuy patients are flown to Darwin through NT Health’s patient travel scheme, which places them and an escort on a 75-minute flight (note: the drive time on unsealed roads is impractical. [see map])

Due to diagnoses at later stages among Aboriginal patients, palliative radiotherapy is slightly more common than radical treatment, according to Keating.

“We aim to treat all cancers as aggressively as possible,” she says. “However, there are some cases in which, part-way through a long RT course, patients may begin to miss appointments because they are finding it hard to be away from family and support networks. We know that breaks in treatment are detrimental to outcomes, so if it becomes a regular occurrence, the consultant will have a discussion with the patient and adjust the fractionation to a more high-dose palliative intent.

“Similarly, with very palliative patients,” Keating adds, “we try to choose the shortest fractionation possible so they can return to their communities. Aboriginal people have a strong connection to the land and when possible, they prefer to die ‘on country.’”

For all curative intent patients, NTRO follows evidence-based guidelines. For example, for hypofractionated breast schedules, they deliver 40 Gy and 15 fractions and may soon switch to an accelerated partial breast irradiation treatment of 27 Gy in five fractions.

“Particularly for our remote patients, if we could treat these patients curatively in five fractions that would be amazing.”

“Particularly for our remote patients, if we could treat these patients curatively in five fractions that would be amazing,” Keating says. “We’re just waiting to see what the evidence looks like.” Although radical radiotherapy’s intent is to cure the Indigenous patient’s cancer, from AWCCC’s establishment in 2010 it was observed that many Indigenous patients found it difficult to attend their treatment appointments on a continual basis. However, the ensuing five years showed a significant improvement in attendance rates at AWCCC, according to a 2019 AWCCC study.2

“Interruptions in a patient’s radiotherapy may lead to compromised treatment outcomes due to the accelerated repopulation of malignant cells,” Keating notes. “Full attendance for the Indigenous group was 76 percent versus 95 percent for non-Indigenous patients.”

The AWCCC investigation indicated that non-attendance was clearly related to higher grades of toxicity associated with higher curative doses compared with palliative radiation.

“A big thing to understand is that there is no word for cancer in the Indigenous language, as it wasn’t a concept pre-colonization,” Hearnden says. “Suddenly, we’re telling these patients there is something that is wrong inside them, though they might not have symptoms. They go for their initial fractions, and they are getting sicker and sicker from the treatment from a side effect standpoint. If you keep showing up every day and you’re getting worse, then why would you keep going?”

The greater relative proximity of NTRO to Aboriginal communities starting in 2010, combined with extensive outreach to NT towns, has seen attendance rates climb, the study indicates. Indigenous attendance during RT has increased over time from 70.6 percent within the first 2.5 years, to 81.6 percent in the following 2.5 years.2 A subsequent assessment of attendance rates is planned for 2025.

Overall, the opening of AWCCC – together with the Cancer Australia initiative and more screening services in remote areas – has resulted in a progressive downward trend in cancer mortality for the greater NT population.1

“This is likely attributed to increased utilization of chemotherapy and radiation therapy as a treatment modality,” she remarks. “Before AWCCC opened, NT patients would have to travel to Adelaide and many patients, especially Aboriginals, chose not to do this. Adelaide is almost like going to Antarctica from Darwin for some of these patients, so they would opt for no treatment or some other less effective therapy, such as palliative RT or chemotherapy alone.”

Increasing capabilities

The year 2025 will usher in a new era of advanced radiotherapy at NTRO with the installation of two Elekta Versa HD systems.

“We look forward to replacing our existing linacs with the Versa HD machines and increasing the options for patients.”

“We look forward to replacing our existing linacs with the Versa HD machines and increasing the options for patients,” Keating says. “We currently are able to deliver SABR lung and SRS brain with the Synergy linacs, but with the sophisticated features of the Versa HD systems, NTRO will be able to do SABR liver and SABR spine.

“We’re not here to try and prove ourselves to anyone, however, we’re just trying to make a difference in the small community that we’re serving,” she stresses. “We want to make these small changes and enhance the quality of life for everyone who comes through the door, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike.”

Elekta supports improvement of Indigenous health with annual award

In April, the Elekta Prize for Commitment to Improving Australian Indigenous Health is awarded to a standout fourth-year Bachelor of Radiation Therapy student at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) who has shown an exceptional understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives. In 2024, the honor went to Anna Chen for her work on the challenges faced by Indigenous patients and her solutions for addressing them.

“In consultation with QUT’s Director of Indigenous Health and a First Nations practitioner, a different patient scenario is crafted,” says Julie Burbery, the Discipline Leader and Senior Lecturer for Radiation Therapy Programs at QUT. “The scenarios are designed to challenge students to consider ethical and legal requirements, social and cultural factors, and more.

“For example, this year’s students had to create their assessment on a fictitious patient scenario concerning a shy 35-year-old Aboriginal woman with three children who was diagnosed with stage 1B1 cervical cancer and lives 1600 km from the radiation center in Mission Beach with her children, new partner, and extended family.”

To ensure accuracy, the QUT team also has the Director of Indigenous Health and an Indigenous radiation therapist thoroughly vet the assessment.

“The vetting process is crucial, as it integrates culturally safe practices into the curriculum, emphasizing the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures in the Australian healthcare setting, Burbury notes. “By embedding these practices throughout the program, our students learn why it is so important to provide culturally safe care to their patients. We are very grateful to have such a strong relationship with Elekta and the support the company provides in sponsoring this final year prize.

“Not only does the award support our graduates,” she adds, “but it also supports future clinicians, providing them with the skills and knowledge to become culturally safe practitioners.”

"Elekta is honored to sponsor the QUT Australian Indigenous Health award,” says Michael Wawrzyniak, Managing Director, Elekta ANZ. “This reflects our commitment to improving understanding and a process for equitable, culturally respectful cancer care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities through our products and our partnerships with our customers. This award is a great representation of this. We thank the healthcare professionals, researchers, and leaders driving progress in this area. Their dedication inspires us to support initiatives that improve access and outcomes for all."

References

- “Cancer in the Northern Territory, 1991-2020.” Fact sheet https://health.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/1171875/cancer-in-the-nt-1991-to-2019.pdf.

- Lovett R, Thurber KA, Maddox R. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking epidemic: what stage are we at, and what does it mean? Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(4):e2741733.

- Carruthers S, Pennefather M, Ward L, et al. Measuring (and narrowing) the gap: The experience with attendance of Indigenous cancer patients for Radiation Therapy in the Northern Territory. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019 Aug;63(4):510-516. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12887. Epub 2019 May 13. PMID: 31081995.

LARNPS241206