Embracing a mindful way to approach cancer and life

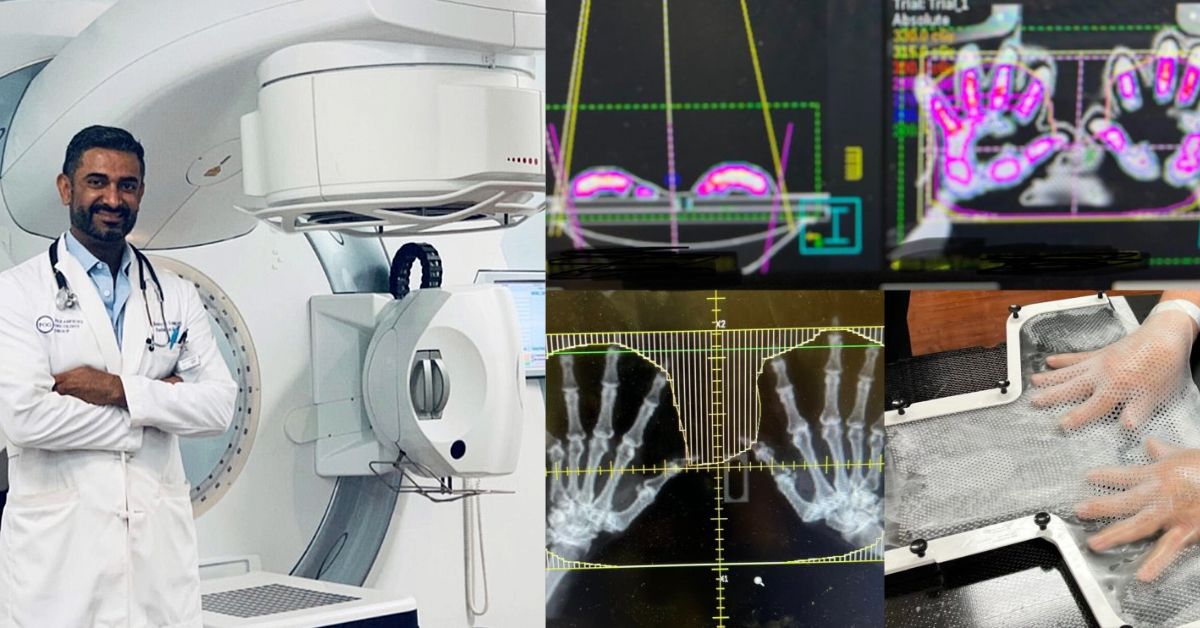

Radiation oncologist harnesses the proven science of mindfulness to help cancer patients, caregivers and others

According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, one of Dr. Ellen Cooke’s mentors, “mindfulness is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us, in the service of self-understanding and wisdom.”

“It’s a way of being, a way that you approach life,” explains Dr. Cooke, a radiation oncologist at Wichita Radiological Group, Wichita, Kansas. “With mindfulness, you’re attending to your life’s experiences through the lens of the present moment, and fostering attitudes of acceptance and non-judgment. An experience doesn’t have to be good or bad – it is what it is.”

She explains that mindfulness is meant to counter what she describes as a person’s “thinking monkey mind.”

“Mindfulness helps you return your attention to the here and now, like focusing on your breathing or the feeling of your feet against the floor, or your weight on a chair…”

“Our minds have a tendency to constantly pull us from the present through thoughts of the past, or worries about the future,” Dr. Cooke explains. “Mindfulness helps you return your attention to the here and now, like focusing on your breathing or the feeling of your feet against the floor, or your weight on a chair – anything that brings you back to the moment.”

Dr. Cooke believes that mindfulness practice can be beneficial to everyone, but may be especially helpful for patients facing a particularly worrisome experience, such as a cancer diagnosis.

She adds that adopting a mindful attitude – per Kabat-Zinn’s definition above – isn’t something that comes naturally to people. However, this skill can be honed through the formal meditation practice that she teaches.

Empirically confirmed

The mindfulness techniques (see “Mindfulness in practice” below) that Dr. Cooke learned and teaches have abundant scientific validation.1-18 On PubMed alone, for instance, there are more than 28,000 entries on the concept of mindfulness and mindfulness studies as of March of 2024.

Dr. Cooke had some knowledge about the value of mindfulness years before and started to direct her patients to mindfulness resources. And facing a period of burnout, she even began using the methods herself.

“I started a daily meditation practice and I noticed such a huge difference in my own life that I began teaching it to patients and others,” Dr. Cooke says. “After my certification through The Mindfulness Center [Bethesda, Maryland], I founded the Circle of Hope in 2019 to inspire and help cancer patients, caregivers and healthcare teams to harness mindfulness. I teach an evidence-based approach that employs the science of mindful awareness to improve the person’s treatment and recovery experience.”

Drawing from her own experience with mindfulness meditation and how it influenced her thinking and emotions, she felt an intense need to confirm the scientific underpinnings of mindfulness.

“The physician part of me wanted evidence. I see that it works, but I wanted to understand why it works and how it works – I didn’t want to practice something blindly.”

“The physician part of me wanted evidence. I see that it works, but I wanted to understand why it works and how it works – I didn’t want to practice something blindly,” she says. “When someone understands how something works, they’re more likely to practice it. Rather than just telling my patients to go home and meditate for 12 minutes, I can tell them that there are actual physical mechanisms that change in the body when they’re practicing routine meditation.”

Mindfulness mechanisms

According to Dr. Cooke, mindfulness impacts four broad categories in an individual: neuroplasticity, biochemical/hormonal changes, epigenetic effects, and physiological effects.

Neuroplasticity

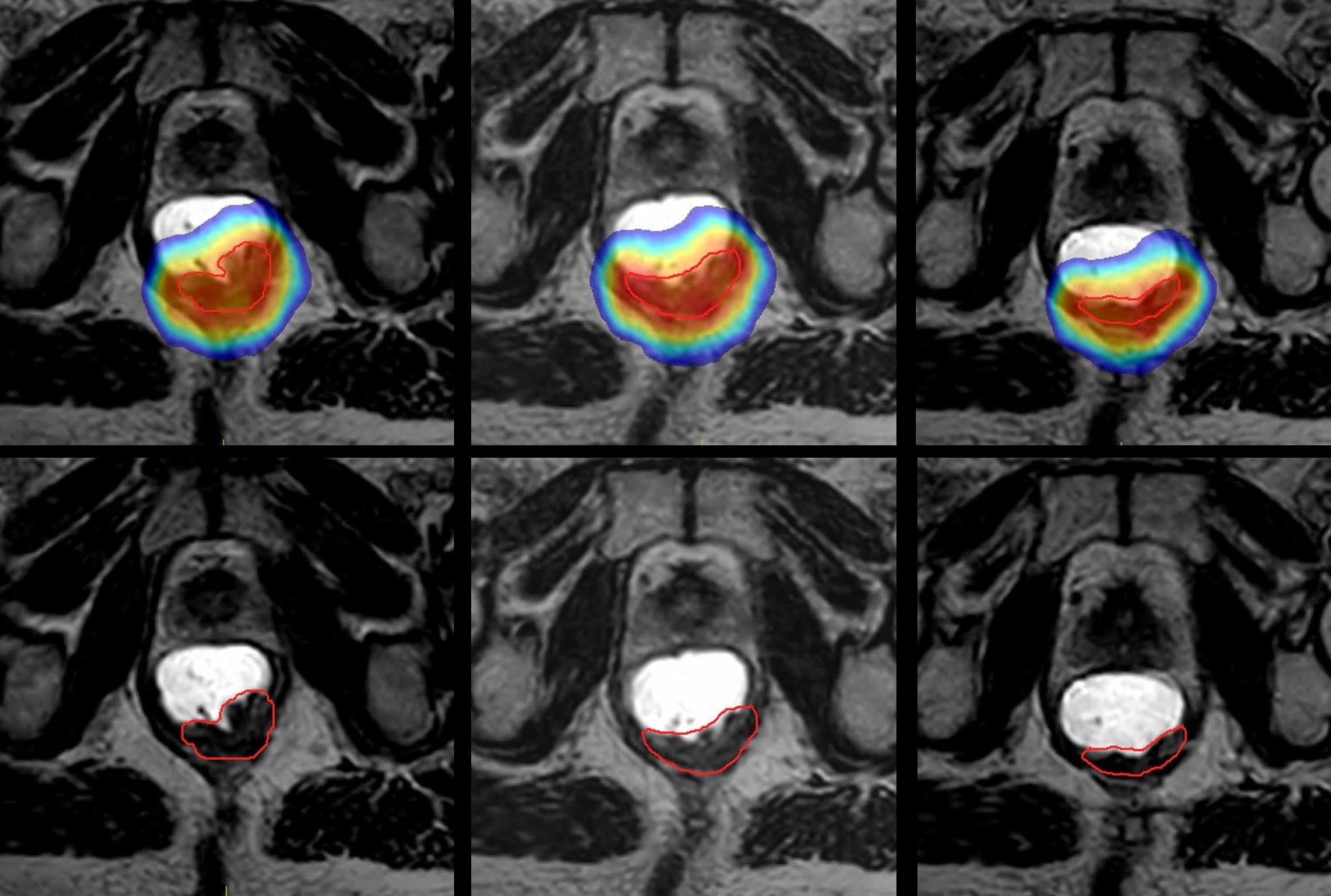

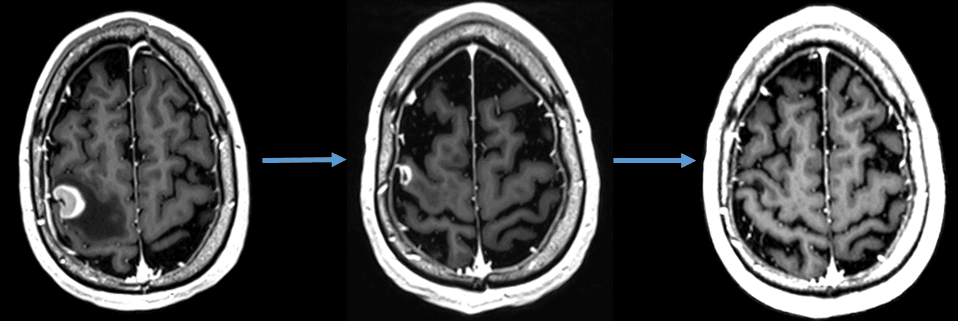

Although the previous scientific understanding was that the brain’s “wiring” didn’t change after a certain age, advanced imaging techniques like functional MRI and PET-CT show that people who are regular meditators can modify neural pathways so that they activate certain regions.

“For example, if you practice meditation that focuses on compassion, we can show with functional imaging that compassion pathways will light up brighter in people who regularly meditate than in those who don’t,”1 she explains. “Some studies on chronic pain used imaging modalities to demonstrate that meditators have a thicker cortex in the brain region associated with lowering pain – these individuals bulked up that part of the brain to make it more active, which helps them perceive that their pain level is lower.”2-4

Clinical studies are thus confirming that regular mindfulness practice results in physical changes to the brain’s structure and activated pathways.

Biochemical/hormonal

Mindfulness has been shown to induce a variety of biochemical and hormonal changes in the body. Particularly relevant for cancer patients, meditation has been shown to lower the levels of the hormone cortisol, helping to reduce stress,5-7 Dr. Cooke notes.

“And oxytocin, the ‘love hormone’ released when a mother is breastfeeding, regulates melatonin, which is involved in the circadian rhythms and the sleep cycles,” she adds. “It increases endorphins, the ‘feel-good’ hormones that exercise is commonly known to induce by reducing inflammation.”8-10

Epigenetic

Everyone is born with a set of DNA that contains genes inherited from their parents, genes that may or may not be expressed.

“Meditation can alter the expression of certain genes through methylation on the chromosomes,” Dr. Cooke explains. “There also is research on the length of telomeres, which are the repeating ends of chromosomes, such that every time a cell divides, a small portion of the genetic material off the end of the chromosome is lost. Studies show that meditation can increase telomere length on the chromosome, actually increasing the cell’s survival, and in turn, improving patient survival.”1,11

Physiological

The two aspects of the central nervous system are the sympathetic nervous system (i.e., fight-or-flight response) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS), which slows the heart rate, dilates blood vessels and decreases pupil size, among other functions.

“The PSNS is sort of the ‘calmer’ of our body,” she observes. “In mindfulness meditation and certain breathing exercises (see “Mindfulness in practice” below), you can actually induce activation of the PSNS to calm the stress response.”12-17

Meditation and guided imagery exercises can also reduce nausea among cancer patients that do not respond to nausea medicine, and also among patients who are experiencing high levels of anxiety and/or depression,18 Dr. Cooke says.

Mindfulness in practice

Dr. Cooke assumes that close to 100 percent of patients diagnosed with cancer experience some level of anxiety, with about 50 percent of her patients availing themselves of mindfulness resources during their treatment journey and in survivorship.

“In my practice, the individuals for whom I tend to specifically recommend mindfulness training are those who voice concerns up front about feeling very concerned about the future, the unknown, fear of dying, anticipating side effects, as well as financial worries, such as the impact on their insurance and their job,” she says.

A specific example is “scanxiety,” unease about an upcoming imaging scan to monitor the progress or surveillance of the cancer.

“Some of my meditations have focused on that time frame, which entails listening to guided recordings to help reduce anxiety,” Dr. Cooke says. “For patients during their radiotherapy course I can recommend various mindfulness interventions designed to address complaints about problems sleeping, claustrophobia or nausea.

“We also have a meditation for patients that have issues on the radiation treatment table, as some patients require a thermoplastic mask that holds the patient’s head firmly on the table – many do not like that,” she continues. “We can give them anxiety medication, of course, but I also have a guided recording that the therapist can play over the speakers in the treatment room.”

As an introduction to mindfulness, patients, healthcare professionals and others can register at the Circle of Hope website to receive a series of seven recorded meditations at no charge (e.g., Introduction to Mindfulness; Stress Reduction; Common Misconceptions, etc.).

Dr. Cooke cites three tangible examples of established mindfulness tactics that she teaches people: the “5-4-3-2-1,” “STOP” and “4-7-8” techniques.

5-4-3-2-1: This method walks through the five senses, with meditators noticing five things they see, four things they hear, three things they feel, two things they smell, and one thing they taste. “As you progress through the senses, it’s basically shutting down the process that was taking you into anxiety and taking you back here to this moment,” she explains. “It totally distracts you from whatever was freaking you out.”

STOP: This technique stands for Stop, Take a Breath, Observe and Proceed Mindfully. As soon as individuals notice they’re fretting about something, it causes them to pause and avoid going down that track, while taking a breath helps them relax. The Observe step helps them acknowledge their thoughts, feeling and environment without judgment, and then they are better able to Proceed Mindfully with intentionality, choosing a response consciously.

4-7-8: A breathing method designed to activate the PSNS. Meditators breathe in to the count of four, hold their breath to the count of seven and then breathe out to the count of eight. A similar breathing technique is called “long exhale.”

“In this method, you breathe in to the count of four, for instance, then breathe out to the count of four. Then on the next breath, you breathe in to the count of four, but extend the exhale to five, and then to six on the next one,” Dr. Cooke explains. “You keep going until the exhale is twice the length of the initial breath. This practice helps distract the mind and also physiologically activates the PSNS, which results in a reduced heart rate and calms the stress response.”

Practicing mindfulness works

While Dr. Cooke hasn’t conducted a formal survey of her patients and others, she does have many anecdotal responses that the practice is indeed helping them, and the techniques have been comprehensively evaluated in the literature.

“The physician scientists that have been studying mindfulness use scales that look at quality of life, stress level, and depression scores. These are evidence-based scales to compare pre- and post-mindfulness intervention and they point to improvements on virtually all fronts,” she says.

“One of the studies13 was a 12-week meditation program in which patients, healthcare professionals and third persons participated. The researchers looked at stress levels, quality of life, and their level of mindfulness skill knowledge. At the end, it showed that all those things had improved with the intervention.”

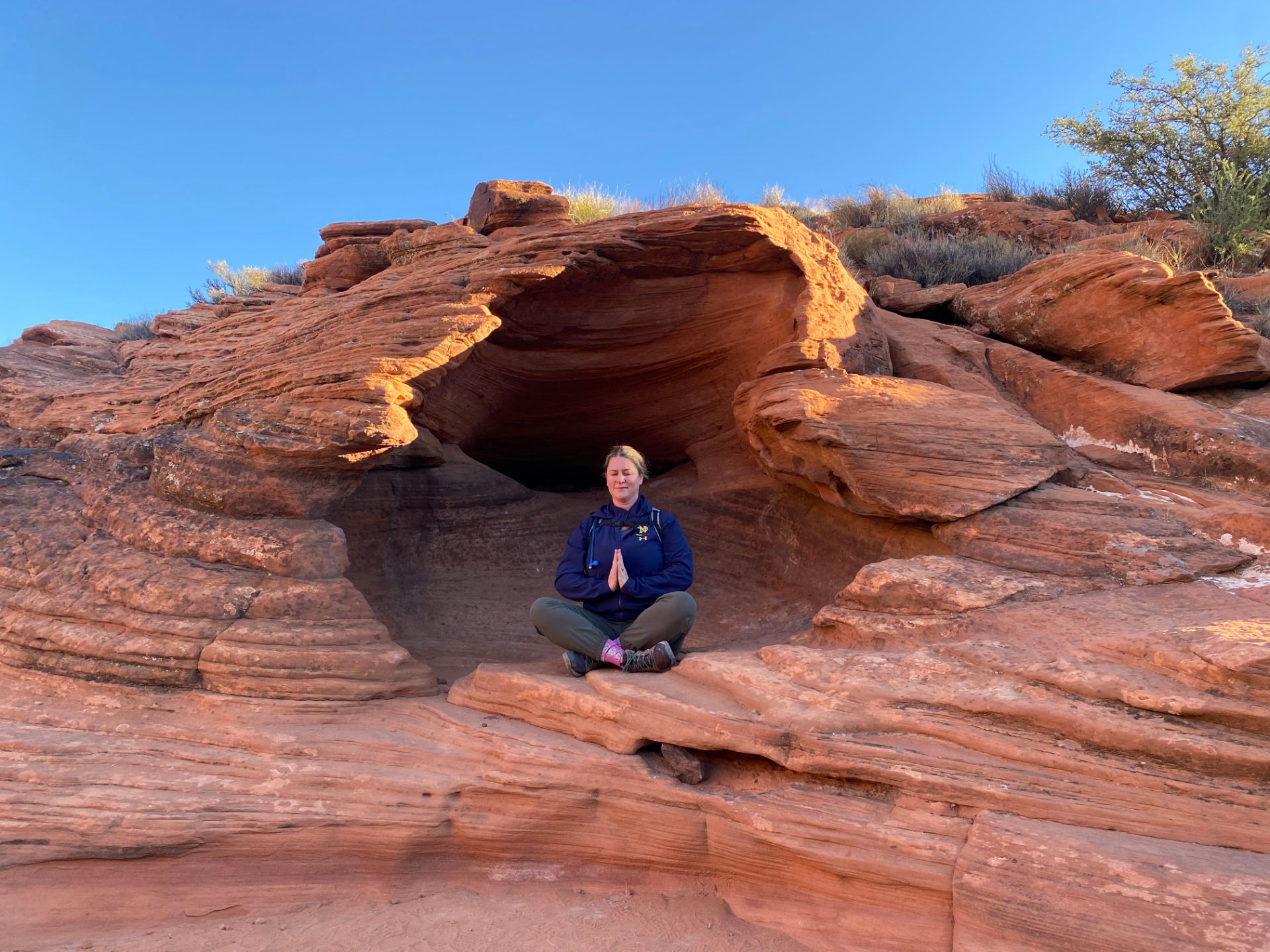

In her personal life, she doesn’t need a randomized controlled trial to appreciate how mindfulness has helped her.

“For me, mindfulness has made life much richer, because things I wouldn’t have noticed before now are the focus of my attention.”

“The whole reason I started Circle of Hope was because of my own experience with meditation practice and how it really led me out of burnout and back to a place where I could take care of patients well again,” Dr. Cooke says. “For me, mindfulness has made life much richer, because things I wouldn’t have noticed before now are the focus of my attention. Let’s say I go for a walk, for example, I used to listen to a podcast and been off in ‘outer space’ and who knows that I was thinking before mindfulness. Now when I go for a walk, I see the birds and I hear them and I feel the breeze. It’s more of an experience.”

References

- Alda M, Puebla-Guedea M, Rodero B, et al. Zen meditation, length of telomeres, and the role of experiential avoidance and compassion. Mindfulness (N Y). 2016;7:651-659. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0500-5. Epub 2016 Feb 22. PMID: 27217844; PMCID: PMC4859856.

- Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, et al. Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport. 2005 Nov 28;16(17):1893-7. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19. PMID: 16272874; PMCID: PMC1361002.

- Grant JA, Courtemanche J, Duerden EG, Duncan GH, Rainville P. Cortical thickness and pain sensitivity in zen meditators. Emotion. 2010 Feb;10(1):43-53. doi: 10.1037/a0018334. PMID: 20141301.

- Lagopoulos J, Xu J, Rasmussen I, et al. Increased theta and alpha EEG activity during nondirective meditation. J Altern Complement Med. 2009 Nov;15(11):1187-92. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0113. PMID: 19922249.

- Turakitwanakan W, Mekseepralard C, Busarakumtragul P. Effects of mindfulness meditation on serum cortisol of medical students. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013 Jan;96 Suppl 1:S90-5. PMID: 23724462.

- Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Naranjo JR, et al. Influence of mindfulness practice on cortisol and sleep in long-term and short-term meditators. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;65(3):109-18. doi: 10.1159/000330362. Epub 2012 Feb 24. PMID: 22377965.

- Black DS, Peng C, Sleight AG, et al. Mindfulness practice reduces cortisol blunting during chemotherapy: A randomized controlled study of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2017 Aug 15;123(16):3088-3096. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30698. Epub 2017 Apr 7. PMID: 28387949; PMCID: PMC5544546.

- Ito E, Shima R, Yoshioka T. A novel role of oxytocin: Oxytocin-induced well-being in humans. Biophys Physicobiol. 2019 Aug 24;16:132-139. doi: 10.2142/biophysico.16.0_132. PMID: 31608203; PMCID: PMC6784812.

- https://osher.ucsf.edu/sites/osher.ucsf.edu/files/inline-files/PPT_UCSF%20Grand%20Rounds%20ZSegal%20April%202023.pdf

- 1Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, et al. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000 Sep-Oct;62(5):613-22. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. PMID: 11020090.

- Carlson LE, Beattie TL, Giese-Davis J, et al. Mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy maintain telomere length relative to controls in distressed breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015 Feb 1;121(3):476-84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29063. Epub 2014 Nov 3. PMID: 25367403.

- Niazi AK, Niazi SK. Mindfulness-based stress reduction: a non-pharmacological approach for chronic illnesses. N Am J Med Sci. 2011 Jan;3(1):20-3. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.320. PMID: 22540058; PMCID: PMC3336928.

- Prevost V, Lefevre-Arbogast S, Leconte A, Delorme C, Benoit S, Tran T, Clarisse B. Shared meditation involving cancer patients, health professionals and third persons is relevant and improves well-being: IMPLIC pilot study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022 May 18;22(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s12906-022-03599-w. PMID: 35585593; PMCID: PMC9116698.

- Mehta R, Sharma K, Potters L, Wernicke AG, Parashar B. Evidence for the role of mindfulness in cancer: Benefits and techniques. Cureus. 2019 May 9;11(5):e4629. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4629. PMID: 31312555; PMCID: PMC6623989.

- Chayadi E, Baes N, Kiropoulos L. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on symptoms of depression, anxiety, and cancer-related fatigue in oncology patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022 Jul 14;17(7):e0269519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269519. PMID: 35834503; PMCID: PMC9282451.

- Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15;113(12):3450-8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. PMID: 19016270; PMCID: PMC2661422.

- Oberoi S, Yang J, Woodgate RL, et al. Association of mindfulness-based interventions with anxiety severity in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3;3(8):e2012598. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12598. PMID: 32766801; PMCID: PMC7414391.

- Charalambous A, Giannakopoulou M, Bozas E, et al. Guided imagery and progressive muscle relaxation as a cluster of symptoms management intervention in patients receiving chemotherapy: A randomized control trial. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 24;11(6):e0156911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156911. PMID: 27341675; PMCID: PMC4920431.

LARNPS240327