Surgeon and inventor: Lars Leksell's brilliant mind

The early years, 1972 - 1986

Reading time: 17 minutes

By applying a neurosurgeon's perspective on technological challenges, Lars Leksell and his team opened a new field: radiosurgery. Learn more about professor Leksell’s innovative work that made these achievements possible.

A successful neurosurgeon, researcher and innovator, Lars Leksell spent his career developing new treatments for disorders of the nervous system. His work would eventually lead to the invention and manufacture of new custom-made instruments that are still used internationally today. Leksell's vision of the "bloodless operation" resulted in his most widely recognized innovation: Gamma Knife.

Tommy and Åsa Bergenheim have spent several years researching Leksell’s life and work, and in their biography Hjärnor och hjärtan (Brains and Hearts) (2021) they portray the versatile researcher and humanist that was Lars Leksell.

“He was very versatile as a researcher,” says Tommy Bergenheim, himself a professor emeritus in neurosurgery. “Lars Leksell’s scientific thinking had a very broad foundation. He must have kept abreast of innovative research in fields that were outside his own main field of neurosurgery. That was one of his strengths: connecting achievements and techniques from different fields of research and devising new applications.”

His son Larry Leksell, who served as Elekta’s CEO for many years, recalls another driving force in his father:

“Dad always kept a strong focus on the patient, a doctor's pathos. He also had an innate drive to make an impact and for his scientific ideas to reach everyday clinical practice.”

A traffic accident turned him onto medicine

The field of medicine, however, was not Lars Leksell’s immediate choice. As a young man, he first leaned towards law or literary history, but after a traffic accident that led to a hospital stay, the doctors and their techniques left an impression on him. He decided to become a doctor himself and was admitted to medical school in the autumn of 1927. But Leksell did not feel passionate about preclinical, theoretical subjects, and he worried before every exam. Yet this changed completely after his bachelor's degree, when he became engrossed in clinical subjects.

In January 1931, Leksell saw one of the foremost Swedish surgeons in action, Herbert Olivecrona, later professor and head of the neurosurgery clinic at the Seraphim Hospital in Stockholm. Olivecrona is said to have operated on over six thousand brain tumor patients over the course of his career. (One of them was the Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy, who described the event in an autobiographical novel, “Journey Round my Skull” (Utazás a koponyám körül) in 1939.)

The encounter set Lars Leksell on his path: he decided to become a neurosurgeon.

However, he had to overcome his aversion to unpleasant smells and bloody operating theatres, says his son Dan Leksell, himself a doctor and for many years active in Elekta.

“Dad was horrified by bloody surgery. In the 1930s, neurosurgery was in its infancy and mortality rates were high. Between 60 and 70 percent of patients died within one month of their procedure. That got my dad wondering whether there might be any less invasive and less traumatic approach brain surgery.”

Lars Leksell had a refined aesthetic sensitivity. In fact, the bloody backdrop of brain surgery became his impetus to change medicine – to make it more aesthetically pleasing and as clean and bloodless as possible.

“Dad was a creative innovator with great ideals of beauty. He liked everything that was beautiful and actively disliked everything that was ugly," says Dan Leksell.

Mixing practice with theory

In 1935, Leksell received his licentiate degree in medicine, which is equivalent to today's medical degree. He now wanted to join his teacher Olivecrona, but the Seraphim Hospital had no vacancies, and Leksell had to seek a position outside the major cities. Over the course of a few years, he gained clinical experience at various hospitals, including Sundsvall Hospital and its renowned surgical clinic. This practical experience was very useful when he later built up his research.

In the autumn of 1938, Lars Leksell finally joined Olivecrona as an assistant physician at the Seraphim Hospital and had the opportunity to carry out his first research activities in a stimulating environment. Leksell apparently realized early on that development in neurosurgery would be dependent on research. Now there were new methods that took advantage of X-rays to visualize the brain. Leksell's first project involved imaging a brain tumor on X-rays using contrast agents. The subject was a rabbit that had a malignant tumor implanted in its brain. Ultimately the technique worked, though the work was never published. In another project, Leksell and a colleague built a device that could measure eye movements using neurophysiological methods.

“This is where his own technical dexterity came into play," says Dan Leksell. “He was an amateur radio builder during his school days and enjoyed it greatly during his early years as a scientist.”

Leksell did not have a dedicated research position, but the system at the time was probably much looser. Tommy Bergenheim explains:

“We don't know exactly how working hours were structured, but there was presumably some allowance for him to slip out of his position as assistant physician from time to time and do research-related things. The cost of facilities and test animals was probably not a problem, and if you worked hard for a period, you could take time off and have space for research.”

Leksell’s first invention: the Leksell rongeur

September of 1939 saw the opening of World War II, and later in the autumn, Finland was invaded by the Soviet Union. Leksell traveled to neighboring Finland and participated as a war surgeon in what later became known as the Finnish Winter War. The precarious conditions in the field led to his first invention, says Dan Leksell.

“They would take shrapnel out of the backs and brains of the soldiers but had very clumsy tools to open the skull and get at the spine. My father developed a pair of rongeurs (heavy-duty forceps) that were double-jointed and that developed a tremendous force when you bring the handles together. Since the war, this tool has been used in every operating theatre around the world and is called the Leksell rongeur. Just say ‘Give me the Leksell’ and everyone will know what to hand the surgeon.”

The Leksell rongeur was Lars Leksell's first product idea. The instrument was developed commercially by the company Stille-Werner, now Stille.

“To my knowledge, my father never received any royalties or other compensation for the rongeur. But he was happy to have made it and that it was put to use," says Dan Leksell.

Finding his field

The Second World War had another direct impact on Leksell's research career. Because of the war, the Finnish-Swedish neurophysiologist Ragnar Granit moved his practice from Helsinki to Stockholm. In August 1940, Granit established a neurophysiology department at Karolinska Institute in premises across the street from Leksell's workplace, the Seraphim Hospital. It was under the future Nobel laureate Granit that Leksell received his actual scientific training, says Tommy Bergenheim. In the years that followed, Granit developed the department into a leading international neuroscience center.

“It was very rewarding for Leksell. He learned experimental techniques and accuracy in a fantastic research environment, and the whole gang eventually became professors.”

Lars Leksell discussed a thesis topic with Granit. A first thought was to continue with eye motor function, but Granit led him to study instead neural impulses in the medulla oblongata, the long stem-like structure that makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It was thought to have some implications on bodily rigidity caused by brain damage. However, the task proved too difficult and after some time Leksell changed his focus to studying the control mechanisms of muscle tension. He investigated the activity of thin motor nerve fibers, the function of which was not yet known. The aim was to develop a better treatment for spastic, disabled children. The experiments included animal testing, and he was able to learn the basics of how to use laboratory animals in medical research, which would prove to be hugely beneficial later on, when he began work in stereotaxy and radiosurgery.

In early May 1945, World War II was finally over and on one of the first days of peace, Lars Leksell presented his doctoral thesis on the thin nerve fibers, which he called gamma motor neurons.

“Dad described how human muscles were controlled, but the thesis met with stiff resistance in the college before it was finally approved. Over time, though, the work became a cornerstone of neurophysiology and is still cited today," says Dan Leksell.

After the war, Leksell left the Seraphim Hospital to start a neurosurgical clinic at the Lund Hospital in southern Sweden. He began to think about increasingly advanced research questions. One such area was psychosurgery. As early as the 19th century, it was hoped that psychiatric disorders and conditions could be influenced by surgical interventions on the brain. In the early 1900s, various treatment methods were developed. A method known as lobotomy would later become notorious. In Sweden, the first lobotomies were performed on patients in the 1940s. The adverse effects of these interventions, such as personality disorders and death, were discovered not long after.

"As a doctor, Leksell was tasked with performing lobotomies himself, but he was critical and dismissed the method as too crude," says Tommy Bergenheim. “He believed that the brain's function instead should be affected by creating small lesions with high-precision placement, so as not to cause excessive damage. His overriding idea was to achieve as non-destructive a technique as possible.”

Stereotaxy rediscovered

Lars Leksell focused on developing new techniques and methods to make psychosurgery more precise without the side effects of lobotomy. One key method was stereotaxy. It involved entering the brain with thin electrodes to record brain activity and disrupt pain pathways or perform other interventions in the depth of the brain.

The process emerged in part from a paper published in England as early as 1908, which described an instrument that could be used to record the activity of the cerebellum (“little brain”) in monkeys. The work had been forgotten for many years, but in the 1940s the stereotactic philosophy was revived.

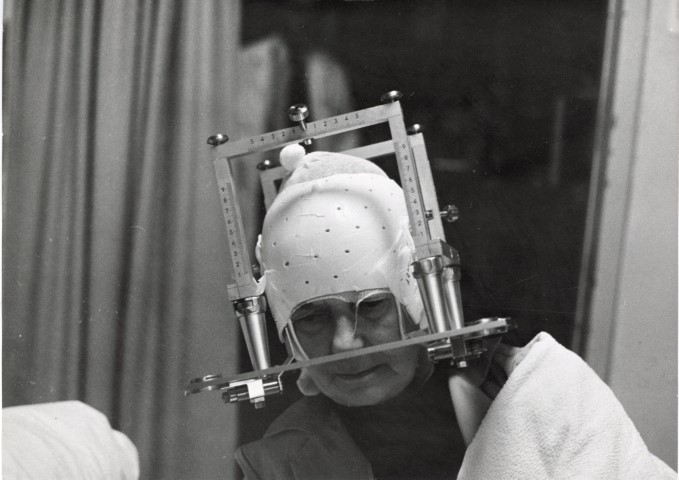

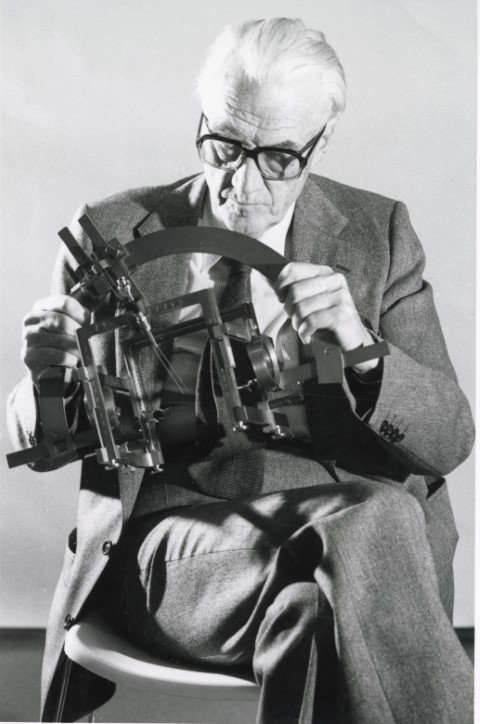

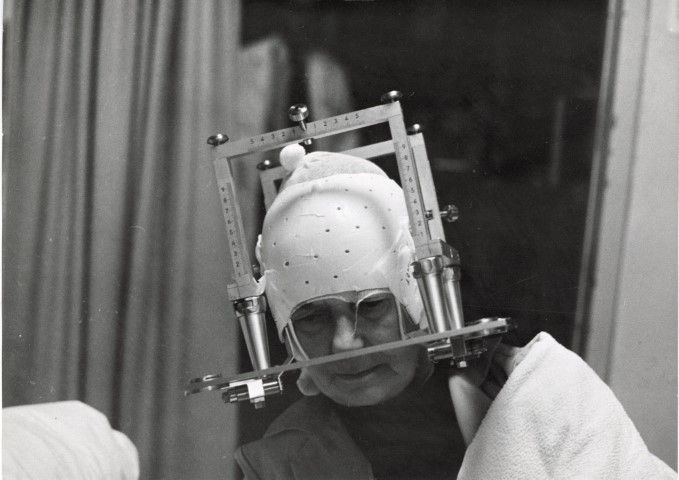

In 1947, Lars Leksell designed his own stereotactic instrument. It used a frame and an arc, which was placed on the patient's head and, using Cartesian coordinates, could be used to create a three-dimensional positioning and calculate a target point with high precision. The design was both functional and aesthetic, says Dan Leksell.

“The Leksell instrument was intuitively designed so that the target point was always in the center of the semicircular arc. It was easy for the surgeon to visualize his task and it has remained a signature of the Leksell instrument to this day.”

Other researchers were working on similar ideas. Lars Leksell reasoned for instance with Hugh Cairns from Oxford and visited Ernest Spiegel and Henry Wycis in Philadelphia. They even let him borrow one of their electrodes. The tip of the electrode, which was placed in the brain, was heated by alternating current and could be used for high-precision ablation of neural pathways. In layman’s terms: it could burn off neural pathways very precisely.

Leksell’s first stereotactic surgery

In 1949, Leksell operated on the first patient using the stereotactic instrument. It was a forty-year-old year old man with a cystic fluid-filled tumor that was pressing on the optic nerve and threatening his vision. Using the instrument, Leksell was able to determine the location of the tumor and drain the cyst. By injecting a radioactive liquid, it was also possible to slow down the growth of the tumor. This proved to be an effective treatment method and is still used today.

In the early 1950s, stereotaxy continued to be developed. Leksell collaborated with Jean Talairach in Paris, among others, and achieved success with various patient groups in Lund. They managed to improve patients with conditions such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression. However, the entire field of psychiatric surgery had fallen into disrepute because of the negative experiences with lobotomy, and Leksell increasingly turned his attention to other areas, says Dan Leksell.

“Stereotaxy was successful in Parkinson's patients and patients with pain. Pain is a theme in dad's memoirs, and he really suffered along with the patients in their pain. It also led him to the idea of replacing electrodes with some form of radiation. His most famous work was published in 1951, in which he explored the possibility of a completely non-invasive surgical approach. This has become one of the most cited works in all of the neurosurgical literature.”

Leksell coined the concept of radiosurgery, which at the time was a ground-breaking idea. His goal was to develop a technique for completely bloodless operations. Using ionizing radiation delivered in a crossfire fashion, lesions could be created in the brain without opening the skull at all. The stereotactic instrument was key to this concept. It provided the coordinates needed to calculate the position of the target and the direction of the radiation.

The radiation used at first was conventional X-ray, but there were also alternatives.

“Lars Leksell also tried to create stereotactic lesions using ultrasound, but this required the removal of the skull bone first, making the procedure too invasive. He would later return to ultrasound in a completely different context to diagnose head injuries," says Tommy Bergenheim.

The first bloodless operation

A few years would still pass before radiosurgery was tried in practice. The first patients were irradiated in 1955.

“It used the original stereotactic frame and arc, to which my father attached a conventional X-ray tube. The X-ray tube could be shifted from left to right along the arc and the arc could be folded forwards and backwards so that the center of the beams always coincided in the middle of the arc," says Dan Leksell.

The initial patients suffered from a severely painful and recurrent facial pain disorder, trigeminal neuralgia.

“Imagine a dentist drilling into the root of your tooth – this gives you an idea of the kind of pain these patients were suffering. But when the patients were seen in follow-up twenty years later, they were still pain-free and doing perfectly well.”

Lars Leksell collaborated with Kurt Lidén, a radiation physicist at Lund University. But Leksell feared that conventional radiation wasn't strong enough to achieve permanent interruption of the neural pathways and therefore considered alternatives.

An American research team led by biophysicist Cornelius Tobias had conducted experiments with proton radiation at UC Berkeley in California. Similar attempts were also made in Sweden by Nobel Prize winner Theodor Svedberg and his young disciple Börje Larsson in Uppsala. Leksell told them about his concept and got them on board for a new research project.

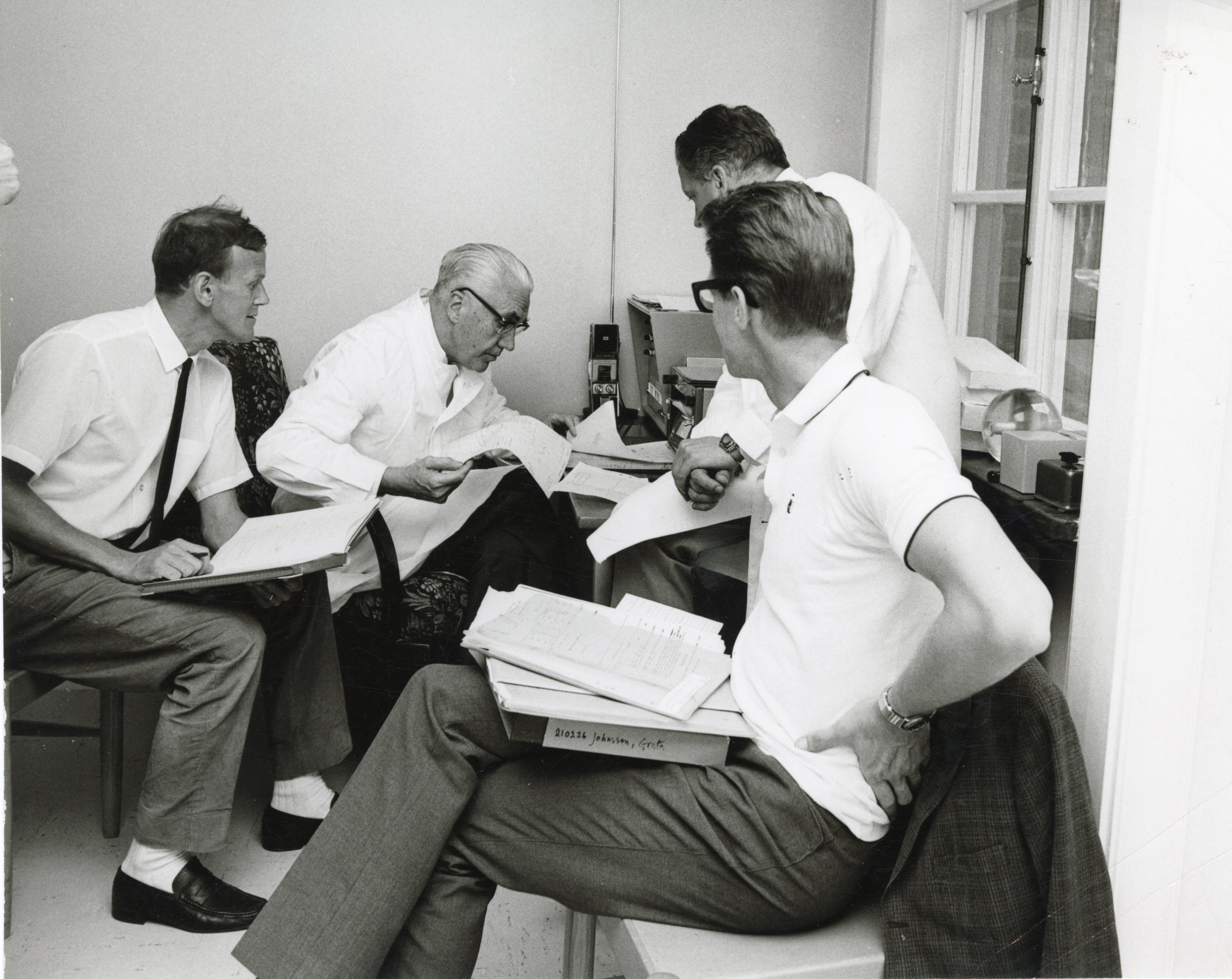

At the time, Börje Larsson was working as a radiation biologist at Gustaf Werner's Institute for Nuclear Chemistry in Uppsala. He now focused on investigating the biological effects of proton radiation in animals, experimenting on rabbits and goats, first on the spinal cord and then on the brain. Test animals were expensive and to keep costs down Larsson acquired a whole farm and tended the animals himself. The analyses of the biological tissue were carried out by Bror Rexed, a distinguished histologist, and many years later a very public figure as General Director of the National Board of Health and Welfare.

“Lars Leksell had an amazing ability to inspire and motivate good people who were experts in research. The people he worked with were always top-notch," says Tommy Bergenheim.

Proton radiation was first tested in November of 1958 on patients with depression, severe pain, and Parkinson's disease in November of 1958. But the method was laborious and had several drawbacks.

“It was a large and costly apparatus to treat each patient. The frame had to be placed on the patient in Stockholm before driving the patient to Uppsala, an hour north - with the stereotactic frame on the patient’s head. With the proton beam, you then rotated the patient and released a dose of radiation, rotated again and irradiated. It took a long time for the patient and was quite burdensome. In addition, it tied up the large research cyclotron so you couldn’t do other work," says Tommy Bergenheim.

An easier way….

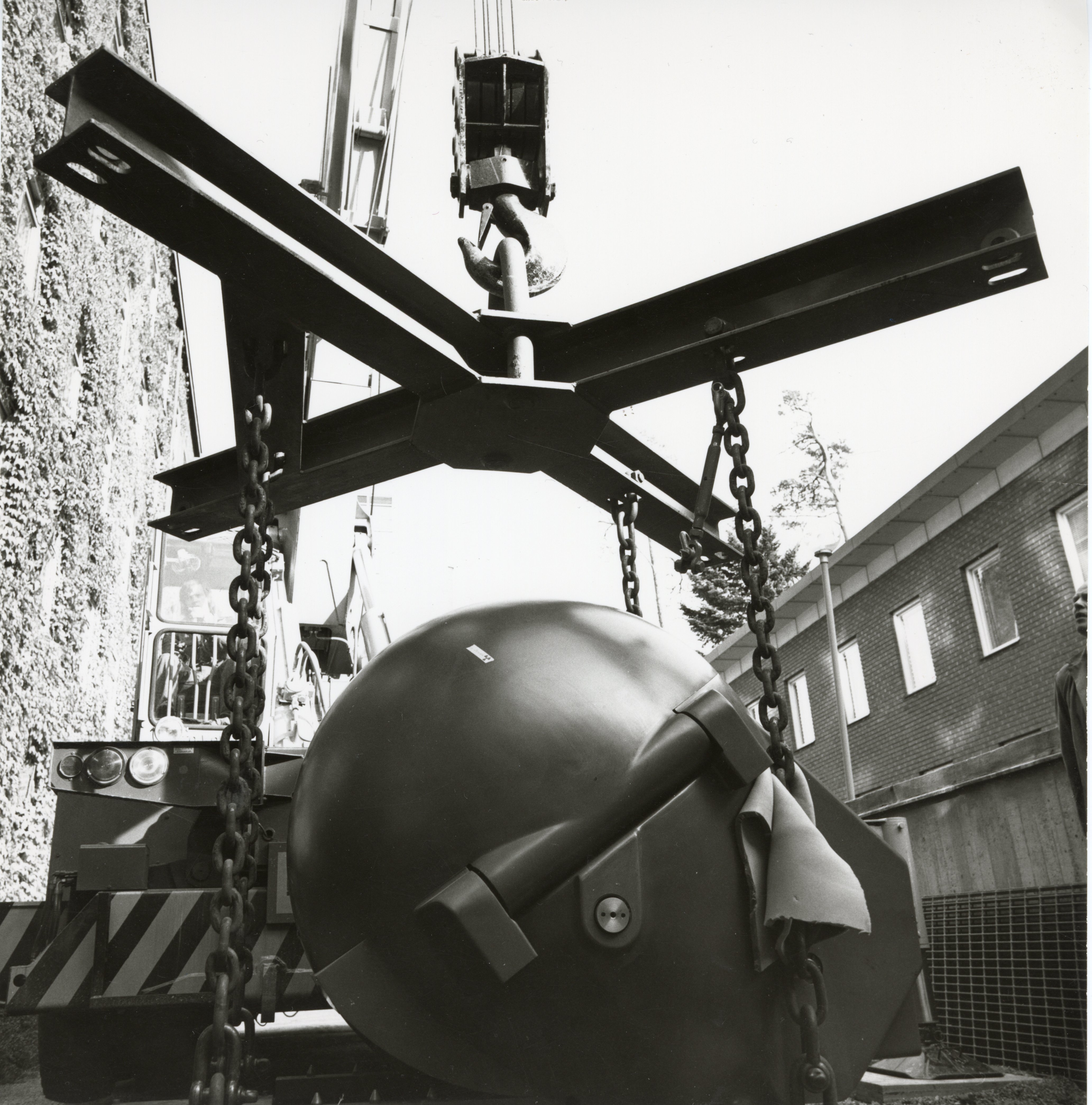

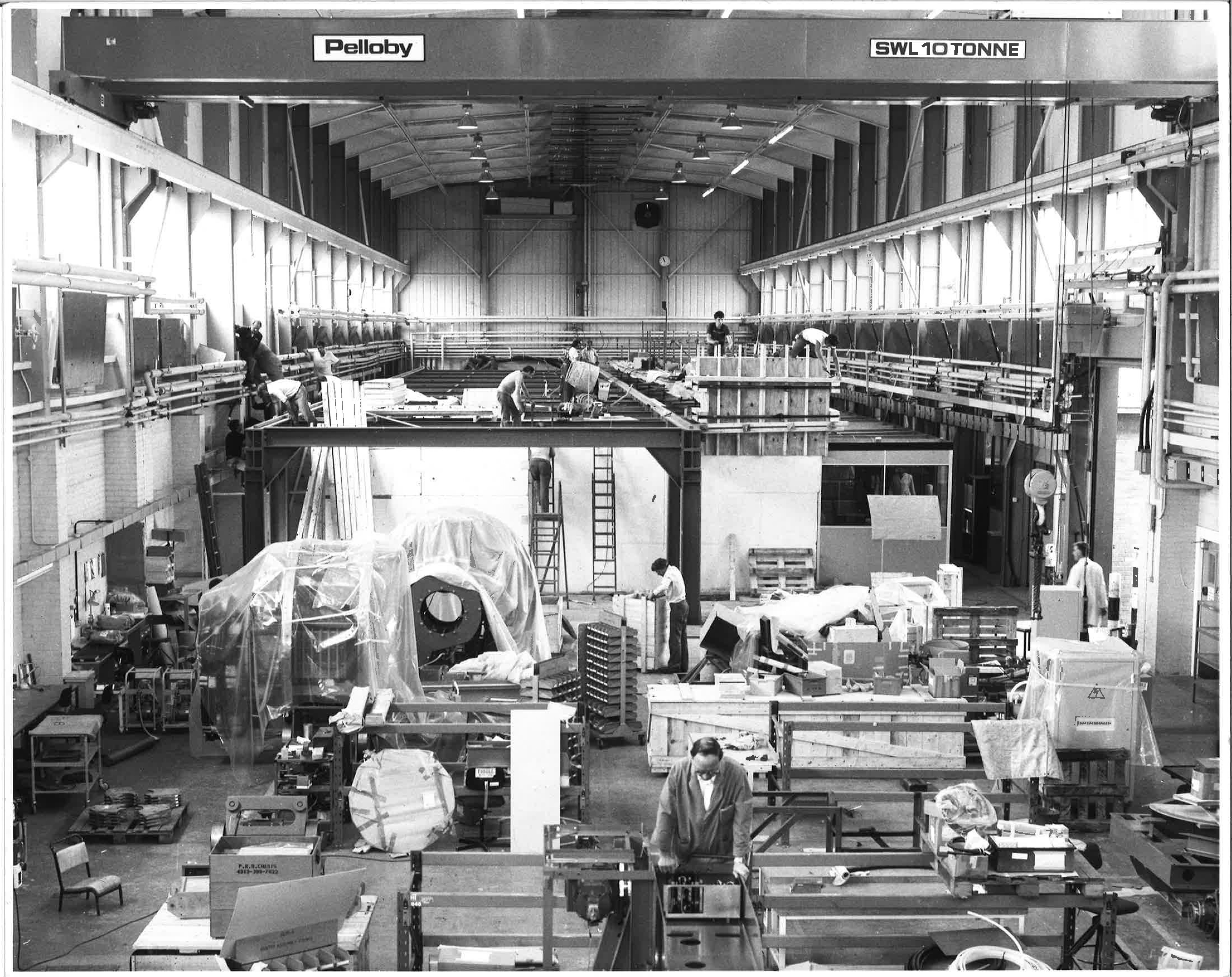

In collaboration with Börje Larsson, Leksell discussed another source of radiation. The choice fell on cobalt-60, gamma radiation, which could be delivered via a specially developed instrument. This would ultimately become Gamma Knife. Research and development of the prototype was largely funded by the Johnson Foundation.

“Dad was a good friend of Bo Axelson Johnson and obtained financial backing for the research. Without that contribution, Gamma Knife would probably never have seen the light of day. In addition, the first machine was manufactured by Motala Verkstad, which was part of the Johnson Group," says Dan Leksell.

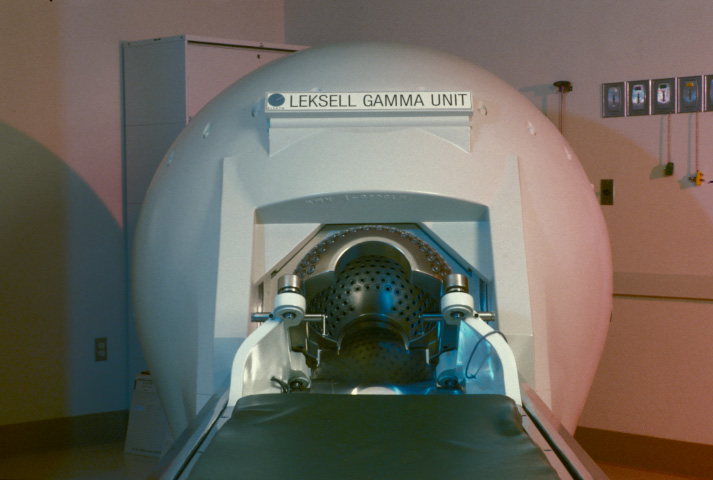

Gamma Knife was based on the stereotactic principle and the theoretical work of Lars Leksell. The first Gamma Knife system was placed in the X-ray clinic at Sophiahemmet Hospital in Stockholm. In January 1968, the first treatment was carried out on a patient with a pituitary tumor, which is a benign type of tumor. In the early years, patients were mainly treated for Parkinson’s disease and pain. The number of patients was also relatively small, says Tommy Bergenheim.

“It all built on the early animal studies, so they were cautious in the beginning and only a few patients were treated, which could be followed-up over several years. Malignant tumors were not treated at all because patients with a metastasis in the brain would die fairly soon from a metastasis elsewhere, even if the brain tumor was successfully irradiated. Leksell was afraid that Gamma Knife would get a bad reputation if it was used to treat such ‘impossible’ cases.”

Gamma Knife builds its reputation

Respect for Lars Leksell's work as a scientist and doctor increased during the years when Gamma Knife was in its experimental and planning stages. He was recommended for personal professorship in Lund, which he took up in 1958. But the promising direction of research in Uppsala made Leksell keen to head back north. In 1960, Herbert Olivecrona retired and Leksell succeeded him as professor at Karolinska Institute and director of the neurosurgery clinic at Seraphim Hospital in Stockholm. A few years later, the clinic relocated to the newly built neuro building in Solna, a suburb of Stockholm, which provided new resources and facilities. Clinical research and healthcare were brought closer together.

Leksell worked closely with the hospital engineers in his research. The path from idea to prototype was not long, recalls Dan Leksell.

“Dad didn't build anything himself, but he had the concepts and made the sketches. I remember how we often had dinner down at Caesar, a local restaurant, and sketched our ideas out on napkins. It could be anything from a new type of forceps to how to make the stereotactic instrument with a quarter arc instead of a half arc. I still have a picture of one of those napkins.”

Later, the sketches were passed on to engineers working at the hospital. Bengt Jernberg drew up plans and Göte Hammarström lathed and milled new parts in his small workshop before the new design was tested in a live situation during surgery.

A legacy like few

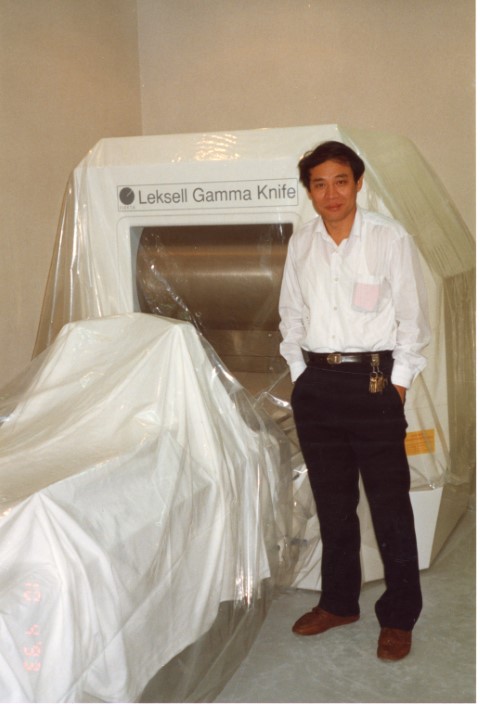

Gamma Knife became Lars Leksell's most famous scientific innovation, but it was based on stereotaxy and his theoretical work. The stereotactic instrument was gradually refined and became Elekta’s' first product when the company was founded. The instrument was manufactured at the time by the company Stålex, and Lars Leksell received no compensation. His son Larry Leksell, who studied economics at the Stockholm School of Economics, figured out that the family could at least act as an intermediary to interested customers. That's how Elekta was born, says Dan Leksell.

“When the company was founded in 1972, it had nothing to do with Gamma Knife. The only revenue Elekta was receiving back then was from the stereotactic instrument, the frame and the arc. We had a single employee, my first wife, who had an office in my father's apartment on Strandvägen in Stockholm. Revenues were modest at first, but there was a royalty income the few times an instrument was sold. Dad himself had no interest in money and wealth.”

Lars Leksell received many awards and prizes for his most famous innovations. But he also made many other important scientific contributions that were not always recognized, says Tommy Bergenheim.

“Radiosurgery was just one field. He also made many other forward-looking discoveries unrelated to Elekta. These include the staining of tumor cells with fluorescent substances during surgery, contrast X-rays of brain tumors and various techniques for opening the skull, in which he was a pioneer. Some of these methods are routinely used in neurosurgery today. They feel so contemporary we often fail to recognize their history. In some cases, they go back to pilot studies that Leksell conducted, work he did not publish but would present at medical conferences or in less formal contexts. Though sometimes uncredited for all his research ideas, he was always eager to point out promising possibilities.”

Did you find it interesting?

Feel free to share it across social media!