Important Turns

1994-2005

Reading time: 16 minutes

A major acquisition paves the way for a broader Elekta way—because radiosurgery and radiotherapy can play well together. Precision is key, as is visualization! For the whole body! This approach requires an organization that truly spans the globe.

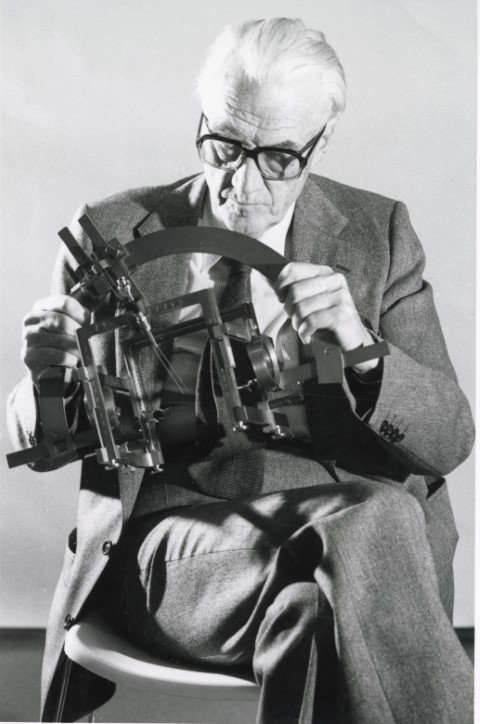

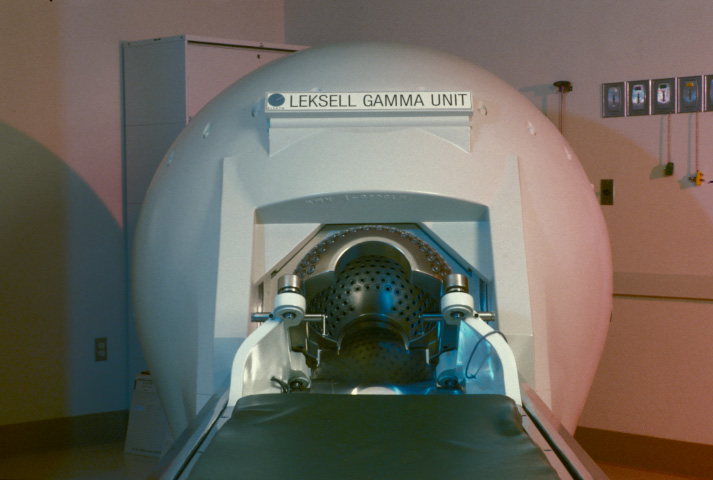

As Elekta turned 20-years-old in 1992, its portfolio held several stereotactic-related products, but of course its core offering was the Gamma Knife. The product, sprung from Professor Lars Leksell’s use of focused gamma-based radiation for brain indications, was at the heart of the company that his son Larry led as CEO and where his other son Danny was a key medical advisor and network builder. The company had however only seen its first real Gamma Knife sale as recently as 1987 – but by now it employed over 150 people with subsidiaries in five countries*. For the year 1991-1992, it made a profit of 26 million SEK, on a turnover of close to 300 million SEK. Its most important markets - USA and Japan – each represented 45 percent of sales

Leksell’s gamma ray method was a noninvasive alternative to creating an opening in the patient’s skull. Media had quickly started calling it “non-bloody brain surgery” —and radiosurgery became a new clinical discipline. Although it could be used for several neurological indications in the head, its reputation soon centered on how it could treat brain cancer.

Radiosurgery differed greatly from radiotherapy, the traditional way of treating cancer. Technically, radiotherapy relied on using linear particle accelerators, or linacs, which generate x-rays and high energy electron beams. It has some downsides compared to Gamma Knife: a treatment field that exposed healthy tissue outside of the target area and the need for multiple sessions—but it had one obvious advantage: it could be used for the whole body.

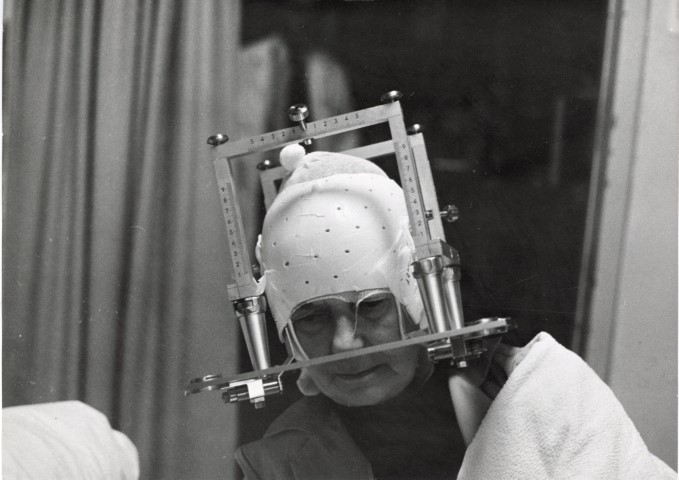

This came quite simply from how bodies functioned. The Gamma Knife “cut” with a high-intensive focused beam, leaving no room for error in hitting the target area. This worked well with the brain, a relatively stable body part. Fixing the patient’s head and using stereotactic equipment further helped create the precise positioning that Gamma Knife needed.

But the rest of the body behaved differently than the brain. A lung, for instance, moved with every breath, shifting the position of any tumor that might be in it. Or a prostate would change in size and position as the bladder filled. Said Larry Leksell: “If the prostate moved a centimeter, and you miss the target area with the Gamma Knife, you'd cut through intestinal walls and most likely cause complications.”

Of course, it would help tremendously if, during treatment, you could see where the beam hit in the body and compensate. But such visualization technology did not exist. (At least not yet. But let’s not get ahead of the historical technical development.) Still, at this point, in the early 1990s, linacs were getting more accurate. They were closing in on doing the same precision work that Gamma Knife had excelled at—and where would that then leave Elekta?

This development made Elekta management consider a bold move—getting its own linear accelerator technology. It would open up more ways to help patients. It would also grow the business, since radiation therapy had a much larger market segment than neurosurgery. Elekta would be able to offer clinics and hospitals a full suite of treatment practices. It would also put the company squarely in the cancer treatment field, and not just have cancer as one of several indications for a cutting-edge method.

“No company wants to be a one-product-wonder. So of course, that drove us when we said, let’s go for the rest of the body.”

Tomas Puusepp, who had joined the company in 1988, had by now a senior sales and operational position. He commented later, “No company wants to be a one-product-wonder. So of course, that drove us when we said, let’s go for the rest of the body.”

The idea had its obvious merits. But it would require additional financing.

Elekta goes public

After the sale of the first Leksell Gamma Knife in 1987, Elekta had decided to not just rely on its own capital for further growth but to take in external funds. In financing rounds in 1988, 1989 and 1992, it raised external equity from institutional investors from Scandinavia, the US and the UK.

These investors, especially the early ones, were now expecting a return on their money. So, while toying with the idea to enter the linac field, Elekta’s management also had to balance this side of the business.

Obviously, one option was to sell Elekta to another corporation, and in that way create the “exit” that the investors sought. But a much more attractive way, they thought, was to list the company on a public stock exchange. It would give the investors an exit opportunity, while also generating more capital for Elekta if it, at the same time, issued new stock.

So, on March 1, 1994, Elekta emitted new shares that began trading on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. The emission had been oversubscribed 15 times, by institutional investors and the public alike. They were drawn to a company that by now had sold 60 Gamma Knife systems, each at an estimated value of 25–30 million SEK. The share price increased by 40% on the first day of trading, ending at 164 SEK per share. By September 1995 it was trading steadily above 300 SEK per share.

Buying an – elephant

In 1994, shortly after the share issue, Elekta started experimenting at Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm with a stereotactic frame for the whole body (and not just for the head), using a linear accelerator as the radiation source. The trials were a success and Elekta decided to acquire its own linear accelerator technology. It was time to embrace broad-based radiation therapy and fully become a cancer treatment provider in the field of radiation oncology.

From a business perspective, it should mean a healthy product expansion. While selling Gamma Knife was profitable at each sale, it took a lot of time, and it was difficult to predict when a customer would finally sign a purchase order. With more classic oncology products, sales would hopefully come more often and be easier to predict. The company would still be selling to highly regulated markets, but they knew how to do that and had already built a good reputation.

In theory this sounded great, but in practice how should Elekta create that linac business? It was quickly decided that developing a linac product line of its own was too time-consuming; an acquisition of existing technology was the only sensible option. But there were only three players in the radiation oncology business from which Elekta could buy the technology: Varian (US), Siemens (Germany) and Philips (Netherlands). And neither were interested in selling or even forming partnerships when Elekta contacted them to explore the idea. Therefore, Elekta started talking with smaller players in the field, such as the Dutch company Nucletron and Swedish Scanditronix, its former licensing partner. Both candidates were deemed not to be a good fit.

Then, an opportunity arose.

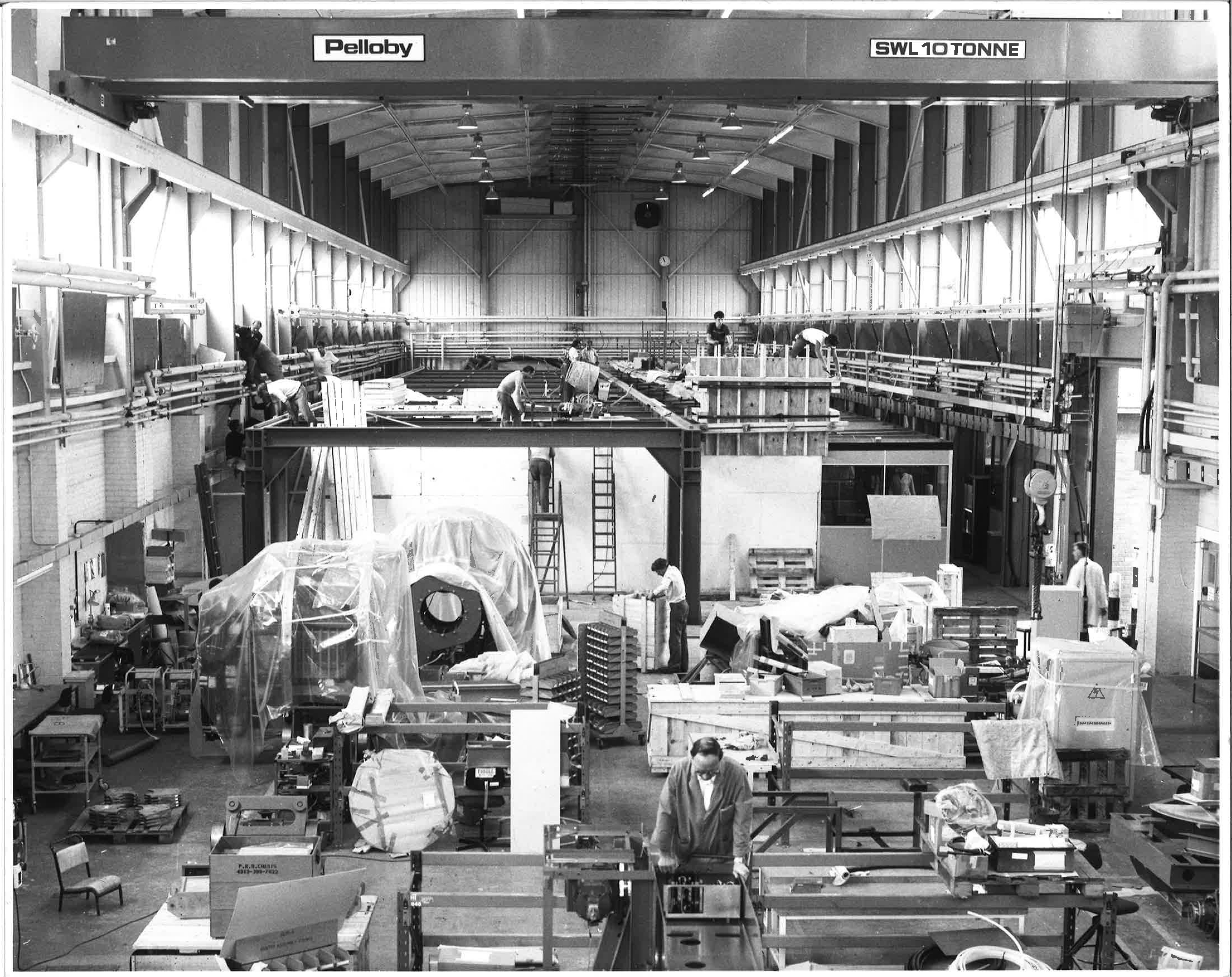

Philips Medical Systems made contact and said they had decided to sell its radiotherapy division, based in Crawley, south of London. It was a research and manufacturing unit that had been working on linear accelerators for years. Philips was losing money on it and wanted to divest. Here was Elekta’s chance to buy technology, and actually also gain access to new geographical markets. Elekta did business mostly in Asia and the US, while Philip’s radiation business had its sales and service network primarily in Europe.

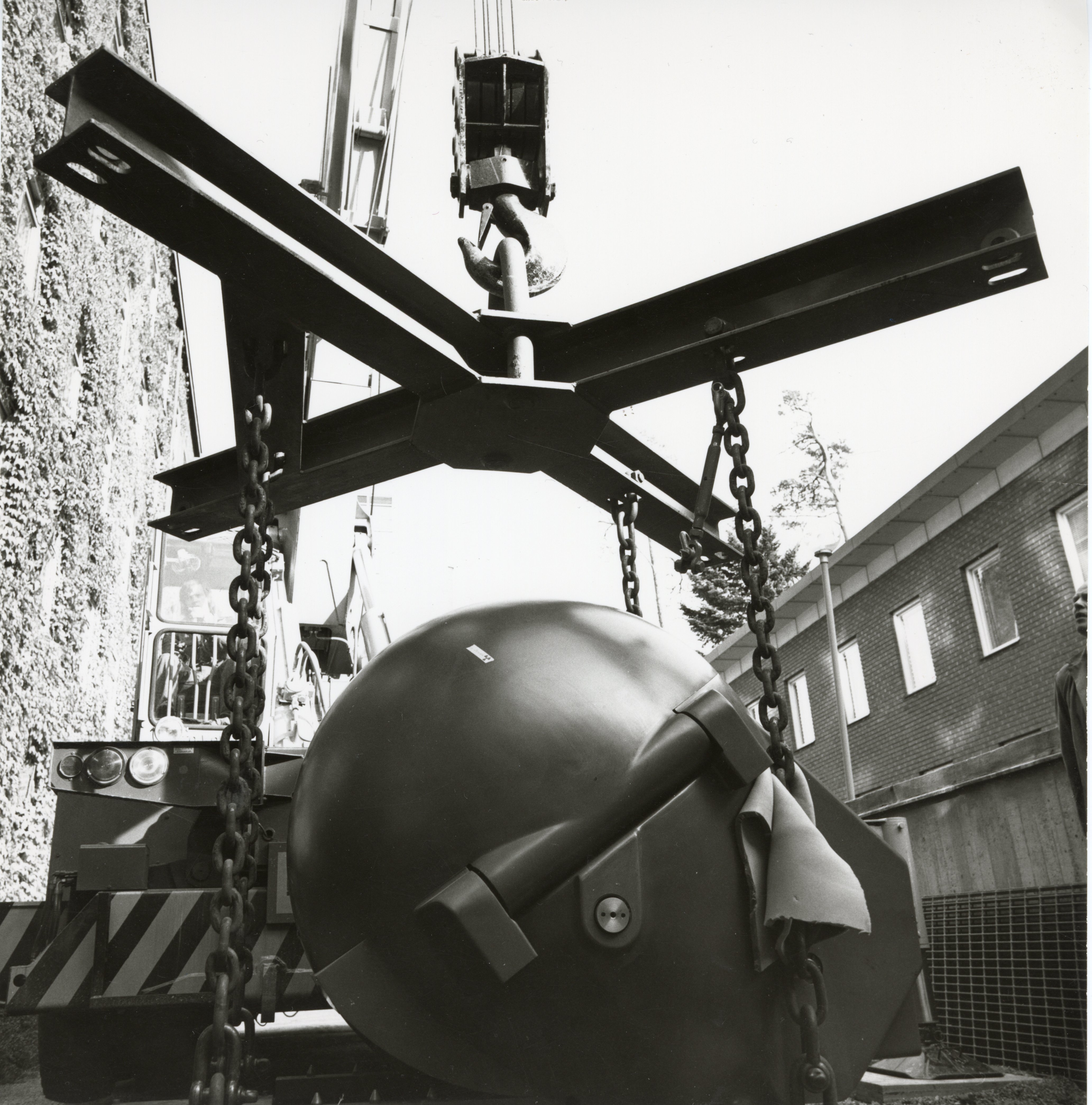

In February 1997, Elekta acquired the radiotherapy business from Philips for approximately 60 million USD. “We worked out a good price,” said Larry later, adding, “but we bought ourselves an awful lot of hard work in order to make the business viable.”

“It was like an ant swallowing an elephant”

Several aspects led to that hard work. For one, there was the scale of the operations in Crawley. Elekta grew from around 250 employees to approximately 1,200 overnight. “It was like an ant swallowing an elephant,” said Tomas Puusepp. Then there was the fact that the two companies made complementary technologies with widely different skillsets among its employees. That meant not much overlap or room for synergies. Their sales approaches were also different, with Elekta selling to neurosurgeons and Crawley to physicists and radiation oncologists.

Dee Mathieson, today a senior vice president at Elekta in charge of product quality, had been with the Philips radiotherapy division for nine years when Elekta acquired it. “‘Elekta,’ we said. ‘Who is that?’ We had never heard about them. But we learned about the treatment technology they had for the brain, and how they wanted to expand for the whole body. And we met Larry, who shared his vision for treating patients. It was like a wet blanket had been lifted, what a boost. We were going to be an important part of this company. In those days we were doing some 40 linacs in Crawley. We now do in excess of 400.”

For Elekta management it was obvious that it would take time to merge the businesses of radiosurgery and radiotherapy, and to create a truly integrated firm. It also became clear, soon after the purchase, that Philips had not really focused on its radiotherapy businesses and that product development, sales and services were lagging behind. “The technology was great, but the quality was not,” said Tomas Puusepp. Elekta would have to invest much more into the Crawley operations than originally planned to lift quality levels.

While Tomas Puusepp was made head of the neuroscience business (“old Elekta”), Volker Stieber was recruited to head the new oncology operations out of Crawley. Stieber was an industry veteran with over 30 years at Siemens where he had built their accelerator business. Puusepp, Stieber and everyone else rolled up their sleeves and went to work.

What they had not prepared for, though, was the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Elekta in Asia

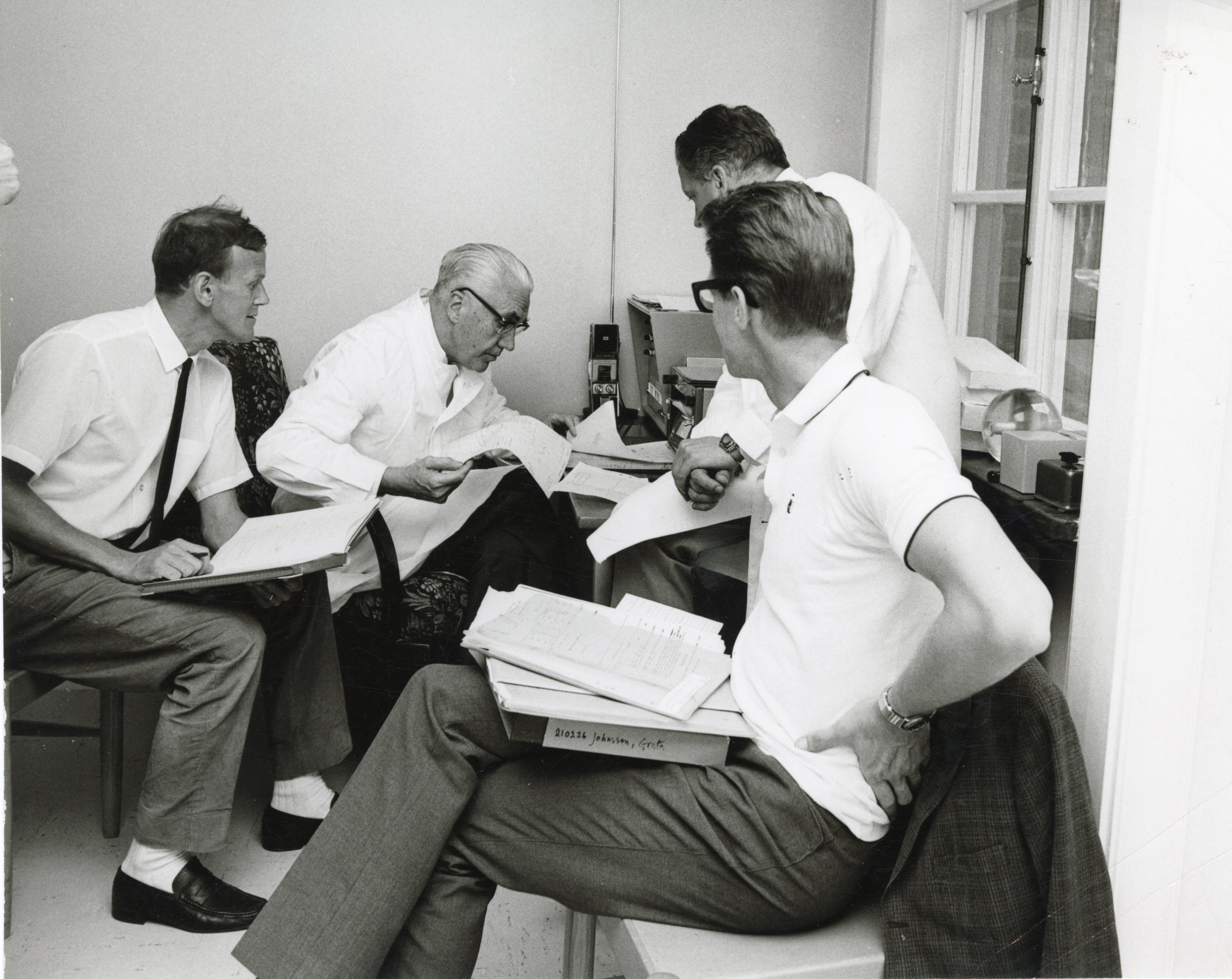

To a large degree, Elekta’s early sales of Gamma Knife had to be built on contacting the disciples of late professor Lars Leksell. They had once been doctoral students to Leksell in Stockholm and then returned home and made their careers at different prestigious medical institutions. The first sales, such as the one to Dr. L. Dade Lunsford at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, were examples of this approach.

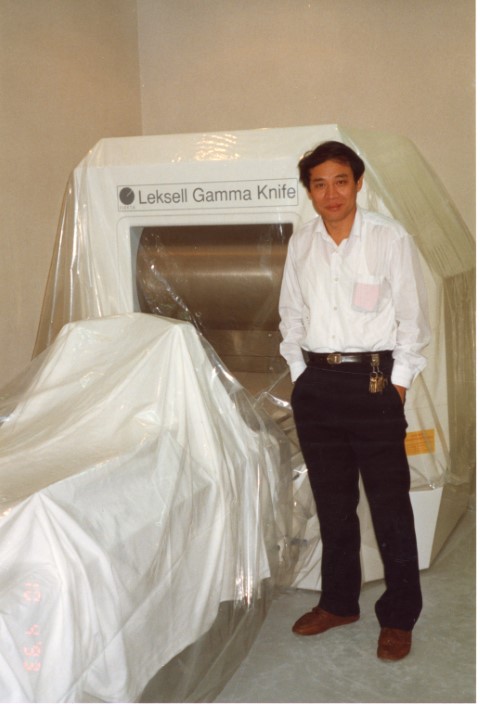

Elekta’s entry into the Asian market, however, followed a different principle. Elekta simply crunched the market numbers and saw countries such as Japan, South Korea and China, all with large populations, that could use radiosurgery and also healthcare systems that could afford this rather expensive equipment.

Rolf Kjellström was instrumental in setting up Elekta's Asian operations. A physicist by education, Rolf been recruited to Elekta in 1988 by Tomas Puusepp and began traveling to China in 1992. In 1994 he moved to Hong Kong and set up Elekta's first Asian-office. He grew the business by identifying leading institutions across the region, establishing relationships and ultimately selling to them. By 1993 the company had sold four systems to China, and in 1996 and 1997 it took orders for twelve more.

Many years later, Rolf said: “My education is in particle physics, but it’s been long since I did calculations on anything other than money. But it’s a good background to have, because I don’t fear anything technical and I understand the questions our customers have.”

The Asian office handled the entire region except for Japan. In Japan, Elekta’s sales presence was handled by Mansson KK, one of the oldest Swedish trading companies in Japan, dating back to 1920. Mansson KK, led by Swedish ex-pat Stig Sundberg, together with Elekta—not the least Danny Leksell who came to live extended periods in Japan—managed to make the first Gamma Knife sale in 1988. They soon landed more orders, and Japan had become Elekta’s second most important market after the United States.

Years later, Danny Leksell summarized the whole process, “Tokyo was key, because that then led pretty quickly to Seoul, which led to Beijing, which led to Taiwan. The Taiwanese and Koreans follow closely what happens in Japan.”

By early 1997, Elekta relied heavily on the Asian market for its income. Close to half the company's sales were in Asia, with an additional half coming from the US and just a small droplet from Europe.

“What's going on, Larry Leksell?”

The 1997 financial crisis began in Thailand and then rolled out across Asia. Elekta's order book quickly evaporated, when its large Asian customers suddenly delayed or straight-up cancelled their orders. Over a couple of months, sales in Elekta's second-largest market pretty much just disappeared.

Elekta management was taken aback. They were already hard at work integrating the Crawley operations, which also cost more money than initially planned. And on top of that, a third area that Elekta had invested heavily in during the past years was becoming an energy and money drain: image-guided surgery (IGS).

Being able to see into the patient’s body during treatment was seen as the next big step for radiation treatment, for radiosurgery and radiotherapy alike. Traditional surgery is traumatic to the body but surgically opening the patient does give the surgeon direct view of the operating area. It was obvious that radiation-based treatments would benefit from better visualization. In the late 1970s, Professor Leksell had already adapted the stereotactic frame to work with the first CT scanner in Sweden; and in the early 1980s, Professor Lunsford in Pittsburgh had installed CT scanners in the operating rooms and conducted radiosurgery via the scanner.

In the early 1990s, Elekta had begun developing its own IGS-program, buying technology companies and entering strategic partnerships. Throughout the 1990s Elekta increased its IGS investments, looking to become the market’s visualization leader. The technology was not limited to just brain use, but also could be used for orthopedics and spine surgery. Early tests showed promise, as did some field tests. But it was costly and would take time.

That the IGS-development was an expensive undertaking was clear to Elekta management, but it was a calculated risk they had been willing to take. Then the opportunity to acquire Crawley came along, which was too good to pass on, but also came with costs. Again, manageable. But suffice it to say, the company did not need more disruption to its existing business. The 1997 Asian financial crisis, however, swept the sales rug out from underneath the company’s feet.

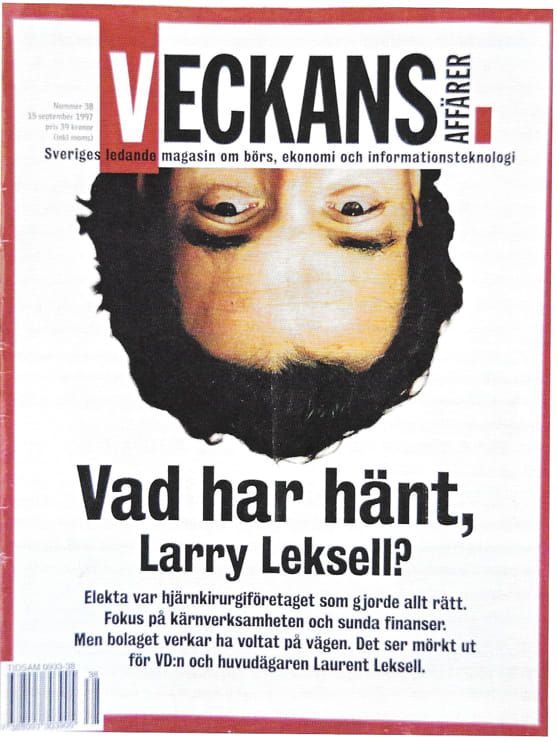

This trifecta of events caused Elekta to post a loss of SEK 49 million for 1996-1997. The markets had been expecting a profit as usual and did not like it. They said Elekta, once focused on just brain surgery, had over-extended itself by going into full-body oncology. They began selling their stock and the Elekta share price fell. In January 1997, it was trading at 230 SEK per share, down from its heights of around 300 SEK per share. By September 1997, it traded at around 130 SEK.

These were rough times for Elekta. Swedish business magazine Veckans Affärer wondered what had happened to “the brain surgery company that we thought could do no wrong.” On the cover of its September 1997 issue, the magazine put an upside-down picture of Larry’s head with the text: “What’s going on, Larry Leksell?”

In the end, the stock price would not bottom out until early 2000, at a share price of about 15 SEK. In 1995, Elekta’s stock market valuation had been 3 billion SEK. By 2000, its market cap was down to 200 million SEK.

During these years, analysts often wondered if Elekta would even survive. At one point in 1997, Larry even offered up his position as CEO to the company board, but they insisted he stay on. Instead, the board and management put in place an action plan to save the company. It prioritized refocusing the strategic aim, divesting unprofitable and unworkable businesses, such as the IGS area, and cutting cost. This inevitably meant reducing staff. Between 1997 and 1999 the workforce was slimmed from around 1250 to 850.

But savings alone would not save Elekta. It had to continue developing the profitable areas of the business. So, with one foot on the brake and one on the gas, Elekta worked its way forward. Through hard sales work and helped by the many practitioners in the field who continued to praise Gamma Knife, the order backlog started to fill up again. By mid-1999, it had built a new order backlog of over SEK 1.1 billion, with sales running at SEK 1.8 billion. There were now some 108 Gamma Knife machines in use globally, with thousands of patients having received radiosurgery. A new Gamma Knife version, “Model C”, had been successfully introduced.

Although the trend was good, Elekta was still posting losses. More was needed. In late 1999, Elekta finally divested the IGS division for 11.75 million USD to American firm Medtronic. The deal built on working together as strategic partners in the future, so Elekta would still have access to imaging technology, just not developed internally. And with this, the company had created its focus—oncology and radiosurgery—after years of trying to break into other fields with an increasingly wide array of products.

It did, however, take another round of refinancing in 1998, and some stern bank negotiations in 2000, before the company felt that the restructuring efforts had fully paid off. Ultimately, most of the people who had been laid-off were offered the opportunity to return—and many of them did.

“The market’s view went from us being stars to idiots and back to stars. Not that we ever were either.”

Many years later, Tomas Puusepp reflected: “We worked insane hours for years and managed to turn the ship around. The market’s view went from us being stars to idiots and back to stars. Not that we ever were either. But the market takes a very black-and-white view on these matters, which doesn’t help when you’re in the slumps.”

Regaining the momentum

What surprised many afterward was that Elekta, even during its toughest times, never cut its research-and-development spending. Typically, that is one of the first areas to go when a company hits hard times. The company had continued developing not just its Gamma Knife offering, but also focused on developing its newly acquired radiotherapy products. Rolf Kjellström commented many years later: “That follows from how we view our business. Knowing the clinical side is key. Without being doctors ourselves, we have to understand how and under what conditions they work. That’s our core strength. We can never lose that.”

“We have to understand under what conditions doctors work. We can never lose that.”

The view also explained why Elekta continued to invest in working closely with customers. “If we’re going to invent technology, we should do it with the people that really understand how it is used. Researchers, academics, clinicians, clients, even competitors. Most of what we’ve put out over the years has been done in collaboration with key clinics through the world,” said Dee Mathieson, herself a trained radiotherapist before joining the medtech field.

By the dawn of the new millennium, Elekta management could now focus more fully on making radiotherapy more precise, more like Gamma Knife radiosurgery. After all, that had been the rationale for acquiring the Crawley radiotherapy outfit in the first place.

One way to achieve this was, in industry jargon, to “conform the radiation field” of the linac. Rephrased: to create a more exact beam and avoid as much healthy tissue around the target area as possible. The term “target area” is somewhat misleading, as it implies a fixed, uniformly shaped zone. In reality, tumors come in all sorts of fluid shapes and what was needed was a radiation beam that could be adapted to each individual target area.

A key device to do this is the multi-leaf collimator (MLC). In general terms, a collimator narrowed a beam of particles or waves. Now, putting “leaves”, made of heavy elements such as tungsten, in front of the beam, and allowing the leaves to move independently, gave the beam different shapes, shapes that would be matched to the target area. Today, MLCs are an integral part of many radiotherapy systems.

Elekta continued development. In 2003 it launched Elekta Synergy®. It was the world’s first system for image guided radiation therapy (IGRT), built on integrating a linear accelerator with high-resolution x-ray imaging. The three-dimensional x-ray images made it possible to visualize the target area during the actual treatment session. It was of course a big step forward in patient treatment, and also showed the markets that although Elekta had sold its IGS business, it had through partnerships kept visualization technology close at hand. Clearly, the company had not given up on its ambitions to provide better visualization during treatment, it had only found new ways to do it.

Granted, x-ray images “only” showed bones and solid structures in the body and didn’t have the exactness of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, which showed soft structures. Still, the real-time visualization that Synergy provided was unprecedented. (A decade later, Elekta would launch Elekta Unity which incorporated MR imaging. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.)

The first Elekta Synergy unit was inaugurated in July 2003 at the Antoni van Leeuwenhoek Hospital in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Gamma Knife also benefitted from this product development. In 2004, Elekta launched the Leksell Gamma Knife 4C, which also had integrated imaging capability, and pooled images from a variety of sources to help clinicians in the pre-treatment planning stages.

The company was truly picking up momentum now. In Asia, particularly in Japan, sales of Gamma Knife had come back to life. The radiotherapy business was churning out products. Eventually, all the Philips legacy linac products were replaced by new designs developed by Elekta in Crawley. The sales and support network had been revamped and quality across the full product and sales process had improved significantly. This was not least important in the US, which still accounted for close to half of the company’s business and where Tomas Puusepp had moved in 2000 to lead customer relations and sales on the ground for a few years.

For fiscal year 2002–2003, Elekta posted its highest operating profit at 323 million SEK, with record order bookings of SEK 3.1 billion and a record order backlog of nearly SEK 2.5 billion. The hardship years were truly behind the company now.

By the time Tomas Puusepp moved back to Stockholm from the US in 2003, there were already discussions regarding him taking over Larry Leksell’s role as CEO. After so many years helming the company that he had been instrumental in founding, and now that the company also was back on solid ground, Larry thought it was a good time to hand over day-to-day reins.

And so, on May 1, 2005, Tomas Puusepp became Elekta’s second CEO. Larry Leksell, still the company's largest shareholder, assumed a new role, focusing on the company’s strategic development, long-term customer relations and expansion into new markets.

And among the many important fields that Elekta—with its long tradition of mechanical solutions and physical products—had to seriously consider was software development.

*Dagens Industri 27 May 1993; and Dagens Industri 6 June 1992

Did you find it interesting?

Feel free to share it across social media!